Last update of this page: January 20, 2026

Containers on LUMI-C and LUMI-G¶

What are we talking about in this chapter?¶

Let's now switch to using containers on LUMI. This section is about using HPC containers on the login nodes and compute nodes and not about building containers for and using containers on LUMI-K, the small OpenShift Kubernetes cloud partition, which delivers less than 0.8% of LUMI's CPU compute power and has no GPUs.

In this section, we will

-

discuss what to expect from containers on LUMI: what can they do and what can't they do,

-

discuss how to get a container on LUMI,

-

discuss how to run a container on LUMI,

-

discuss some enhancements we made to the LUMI environment that are based on containers or help you use containers,

-

and pay some attention to the use of some of our pre-built AI containers.

If you are interested in doing AI on LUMI, we highly recommend that you have a look at the AI course materials developed by the LUNI User Support Team.

Remember though that the compute nodes of LUMI are an HPC infrastructure and not a container cloud! HPC has its own container runtimes specifically for an HPC environment and the typical security constraints of such an environment.

What do containers not provide¶

What is being discussed in this subsection may be a bit surprising. Containers are often marketed as a way to provide reproducible science and as an easy way to transfer software from one machine to another machine. However, containers are neither of those and this becomes very clear when using containers built on your typical Mellanox/NVIDIA InfiniBand based clusters with Intel processors and NVIDIA GPUs on LUMI. This is only true if you transport software between sufficiently similar machines (which is why they do work very well in, e.g., the management nodes of a cluster, or a server farm).

First, exact reproducibility is a myth. Computational results are almost never 100% reproducible because of the very nature of how computers work. If you use any floating point computation, you can only expect reproducibility of sequential codes between equal hardware. As soon as you change the CPU type, some floating point computations may produce slightly different results, and as soon as you go parallel this may even be the case between two runs on exactly the same hardware and with exactly the same software. Besides, by the very nature of floating point computations, you know that the results are wrong if you really want to work with real numbers. What matters is understanding how wrong the results are and reproduce results that fall within expected error margins for the computation. This is no different from reproducing a lab experiment where, e.g., each measurement instrument introduces errors. The only thing that containers do reproduce very well, is your software stack. But not without problems:

Containers are certainly not performance portable unless they have been specifically designed to run optimally on a range of hardware and your hardware falls into that range. E.g., without proper support for the interconnect it may still run but in a much slower mode. But one should also realise that speed gains in the x86 family over the years come to a large extent from adding new instructions to the CPU set, and that two processors with the same instructions set extensions may still benefit from different optimisations by the compilers. Not using the proper instruction set extensions can have a lot of influence. At my local site we've seen GROMACS doubling its speed by choosing proper options, and the difference can even be bigger.

Many HPC sites try to build software as much as possible from sources to exploit the available hardware as much as possible. You may not care much about 10% or 20% performance difference on your PC, but 20% on a 160 million EURO investment represents 32 million EURO and a lot of science can be done for that money...

But even basic portability is a myth, even if you wouldn't care much about performance (which is already a bad idea on an infrastructure as expensive as LUMI). Containers are really only guaranteed to be portable between similar systems. When well built, they are more portable than just a binary as you may be able to deal with missing or different libraries in the container, but that is where it ends. Containers are usually built for a particular CPU architecture and GPU architecture, two elements where everybody can easily see that if you change this, the container will not run. But there is in fact more: containers talk to other hardware too, and on an HPC system the first piece of hardware that comes to mind is the interconnect. And they use the kernel of the host and the kernel modules and drivers provided by that kernel. Those can be a problem. A container that is not build to support the SlingShot interconnect, may fall back to TCP sockets in MPI, completely killing scalability. Containers that expect the knem kernel extension for good intra-node MPI performance may not run as efficiently as LUMI uses xpmem instead.

But what can they then do on LUMI?¶

Containers are in the first place a software management instrument.

-

A very important reason to use containers on LUMI is reducing the pressure on the file system by software that accesses many thousands of small files (Python and R users, you know who we are talking about). That software kills the metadata servers of almost any parallel file system when used at scale.

As a container on LUMI is a single file, the metadata servers of the parallel file system have far less work to do, and all the file caching mechanisms can also work much better.

-

Software installations that would otherwise be impossible. E.g., some software may not even be suited for installation in a multi-user HPC system as it uses fixed paths that are not compatible with installation in module-controlled software stacks. HPC systems want a lightweight

/usretc. structure as that part of the system software is often stored in a RAM disk, and to reduce boot times. Moreover, different users may need different versions of a software library so it cannot be installed in its default location in the system software region. However, some software is ill-behaved and cannot be relocated to a different directory, and in these cases containers help you to build a private installation that does not interfere with other software on the system.They are also of interest if compiling the software takes too much work while any processor-specific optimisation that could be obtained by compiling oneself, isn't really important. E.g., if a full stack of GUI libraries is needed, as they are rarely the speed-limiting factor in an application.

-

As an example, Conda installations are not appreciated on the main Lustre file system.

On one hand, Conda installations tend to generate lots of small files (and then even more due to a linking strategy that does not work on Lustre). So they need to be containerised just for storage manageability.

They also re-install lots of libraries that may already be on the system in a different version. The isolation offered by a container environment may be a good idea to ensure that all software picks up the right versions.

-

An example of software that is usually very hard to install is a GUI application, as they tend to have tons of dependencies and recompiling can be tricky. Yet rather often the binary packages that you can download cannot be installed wherever you want, so a container can come to the rescue.

-

Another example where containers have proven to be useful on LUMI is to experiment with newer versions of ROCm or the Cray Programming Environment than we can offer on the system.

This often comes with limitations though, as (a) that ROCm version is still limited by the drivers on the system and (b) we've seen incompatibilities between newer ROCm versions and the Cray MPICH libraries.

-

And a combination of both: LUST with the help of AMD have prepared some containers with popular AI applications. These containers use some software from Conda, a newer ROCm version installed through RPMs, and some performance-critical code that is compiled specifically for LUMI.

-

Isolation is often considered as an advantage of containers also. The isolation helps preventing that software picks up libraries it should not pick up. In a context with multiple services running on a single server, it limits problems when the security of a container is compromised to that container. However, it also comes with a big disadvantage in an HPC context: Debugging and performance profiling also becomes a lot harder.

In fact, with the current state of container technology, it is often a pain also when running MPI applications as it would be much better to have only a single container per node, running MPI inside the container at the node level and then between containers on different nodes.

Remember though that whenever you use containers, you are the system administrator and not LUST. We can impossibly support all different software that users want to run in containers, and all possible Linux distributions they may want to run in those containers. We provide some advice on how to build a proper container, but if you chose to neglect it it is up to you to solve the problems that occur.

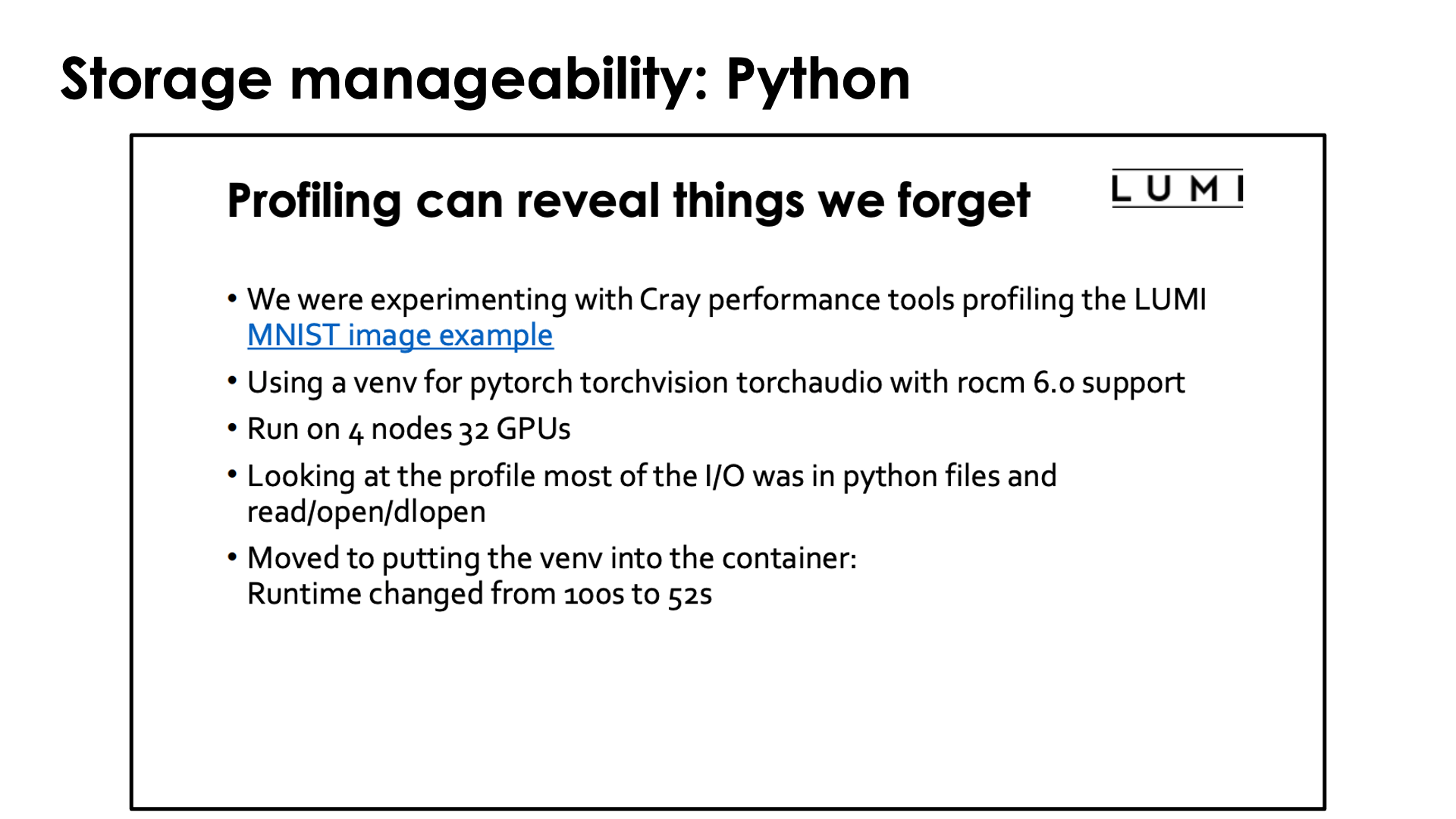

In case you wonder how important it is to containerise Conda and Python installations: Look no further than the slide above which was borrowed from the presentation "Loading training data on LUMI" of the "Moving your AI training jobs to LUMI of October 2025 and was presented by our colleagues from the HPE Center of Excellence supporting LUST. They wanted to see to what extent their profiling tools were useful to understanding the performance of AI jobs and took a simple example from the LUMI documentation. The conclusion of the profiling was a bit surprising, even for them. It turned out that in this rather standard example for machine learning (well, not so standard for what many users try as the MNIST dataset is not stored as many small files, but the tasks are standard) Python was spending as much time reading in Python code from Lustre as it was doing useful work. Containerising the Python installation sped up the benchmark from 100s to 52s.

Managing containers¶

Not all container runtimes are a good match with HPC systems and the security model on such a system. On LUMI, we currently support only one container runtime.

Docker is not available, and will never be on the regular compute nodes as it requires elevated privileges to run the container which cannot be given safely to regular users of the system.

Singularity Community Edition is currently the only supported container runtime and is available on the login nodes and the compute nodes. It is a system command that is installed with the OS, so no module has to be loaded to enable it. We can also offer only a single version of singularity or its close cousin AppTainer as singularity/AppTainer simply don't really like running multiple versions next to one another, and currently the version that we offer is determined by what is offered by the OS. Currently we offer Singularity Community Edition 4.1.3. The reason to chose for Singularity Community Edition rather than Apptainer is that it supports a build model that is compatible with the security restrictions on LUMI and is not offered in Apptainer.

To work with containers on LUMI you will either need to pull the container from a container registry,

e.g., DockerHub, bring in the container either by creating a tarball from a

docker container on the remote system and then converting that to the singularity .sif format on LUMI

or by copying the singularity .sif file, or use those container build features of singularity

that can be supported on LUMI within the security constraints

(which is why there are no user namespaces on LUMI).

Singularity does offer a command to pull in a Docker container and to convert it to singularity format. E.g., to pull a container for the Julia language from DockerHub, you'd use

singularity pull docker://julia

Singularity uses a single flat sif file for storing containers. The singularity pull command does the

conversion from Docker format to the singularity format.

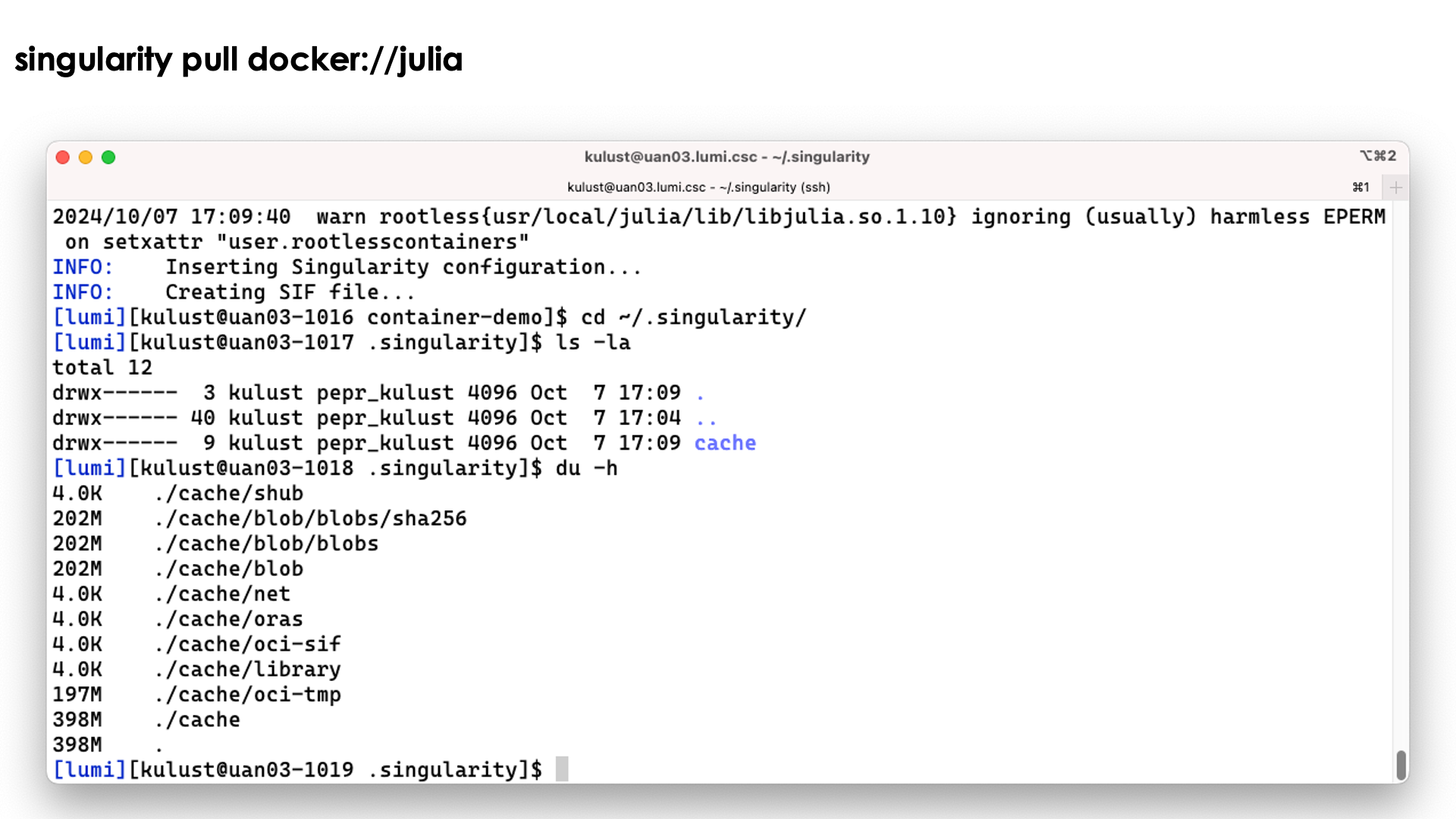

Singularity caches files during pull operations and that may leave a mess of files in

the .singularity cache directory. This can lead to exhaustion of your disk quota for your

home directory. So you may want to use the environment variable SINGULARITY_CACHEDIR

to put the cache in, e.g,, your scratch space (but even then you want to clean up after the

pull operation so save on your storage billing units).

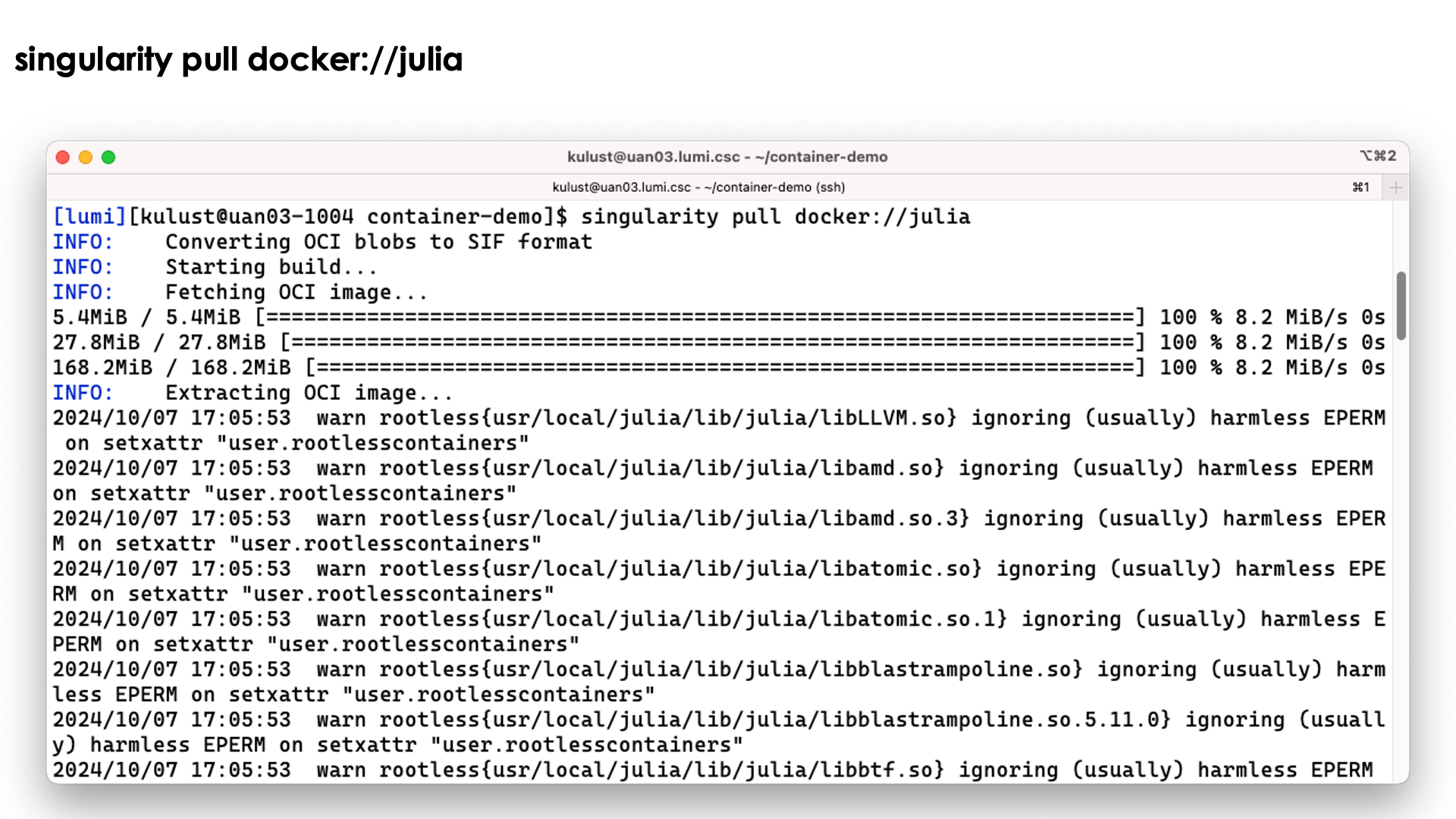

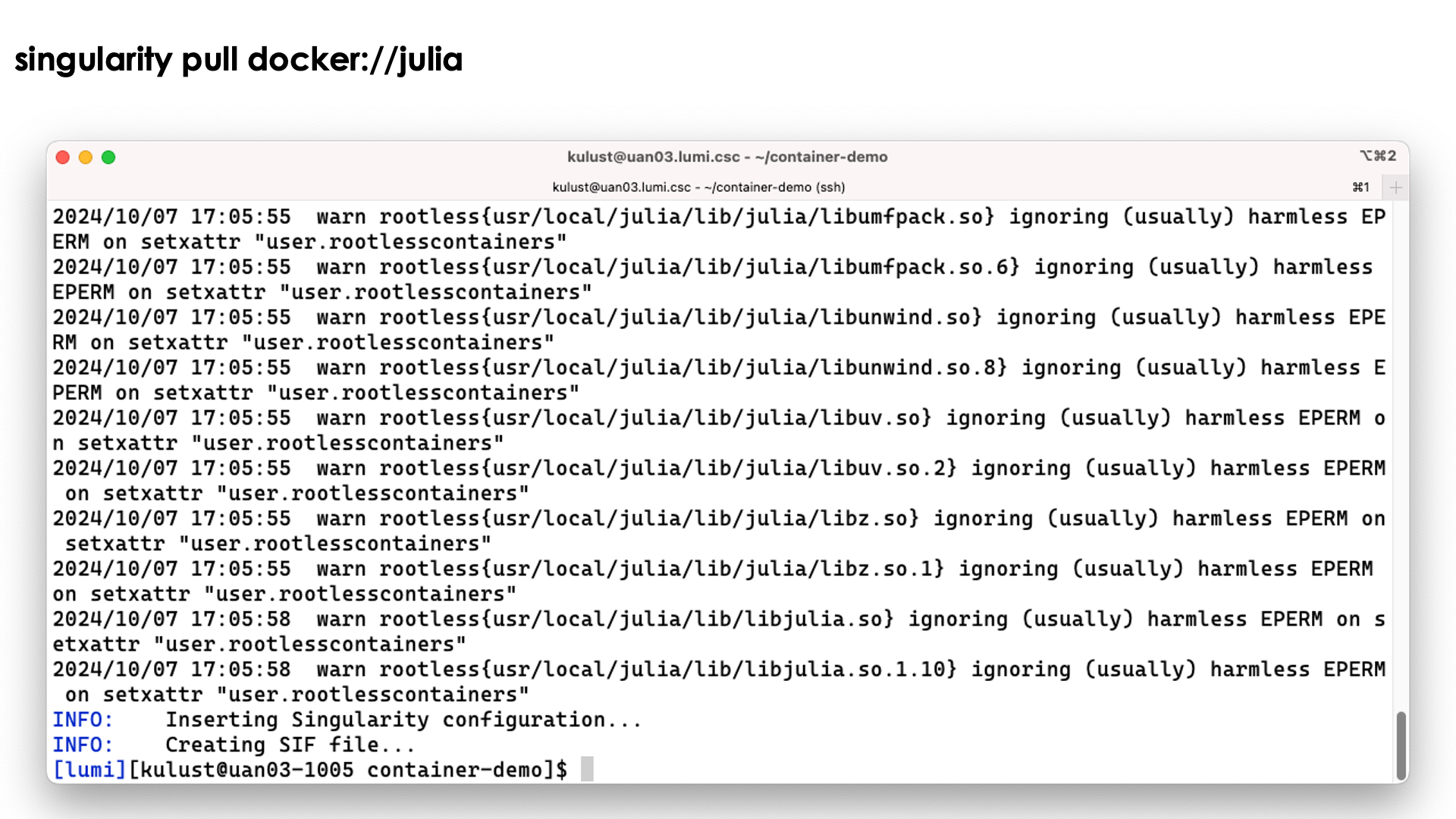

Demo singularity pull

Let's try the singularity pull docker://julia command:

We do get a lot of warnings but usually this is perfectly normal and usually they can be safely ignored.

The process ends with the creation of the file jula_latest.sif.

Note however that the process has left a considerable number of files in ~/.singularity also:

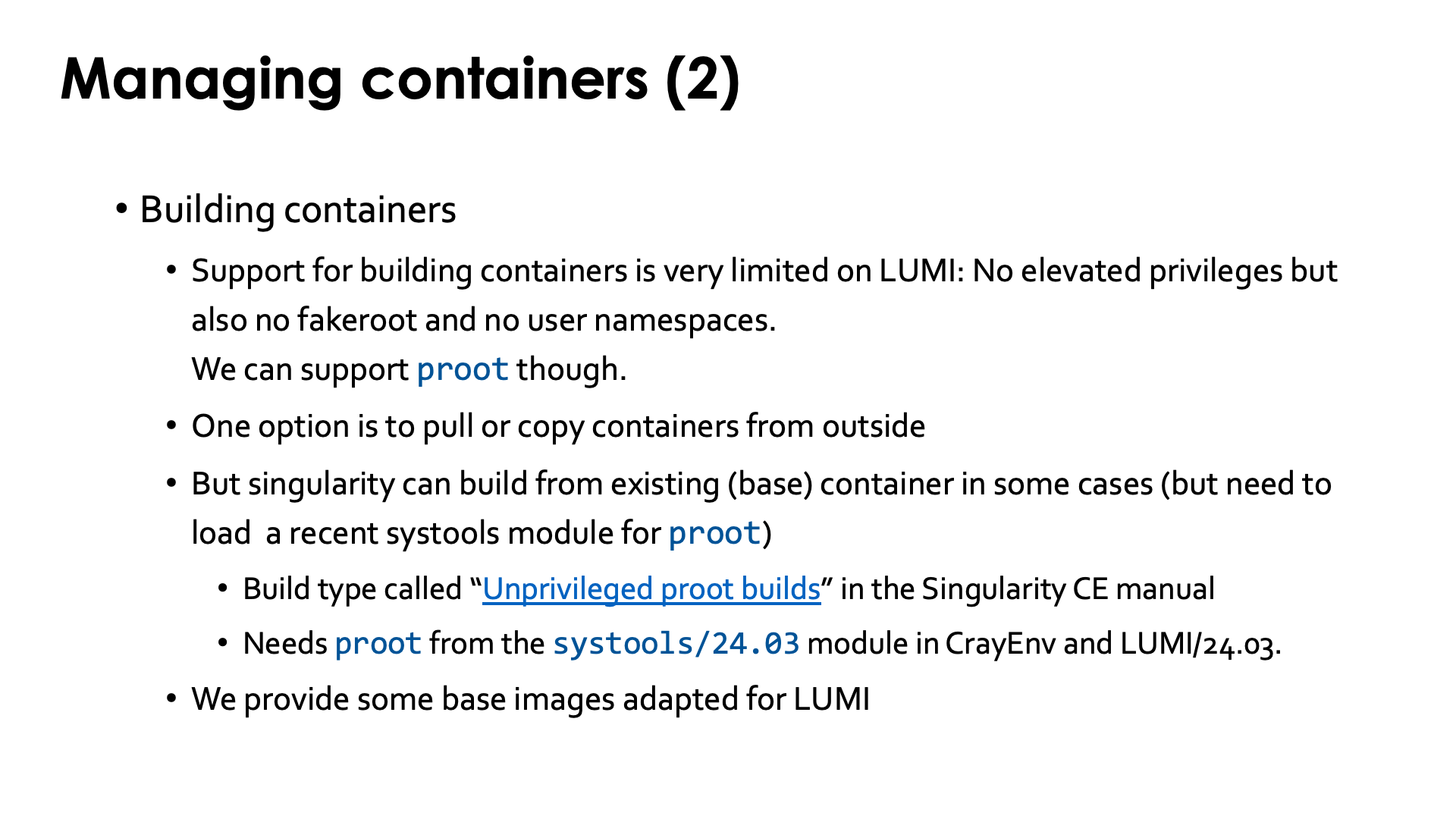

There is currently limited support for building containers on LUMI and I do not expect that to change quickly. Container build strategies that require elevated privileges, and even those that require user namespaces, cannot be supported for security reasons (as user namespaces in Linux are riddled with security issues when used in combination with networked file systems). Enabling features that are known to have had several serious security vulnerabilities in the recent past, or that themselves are unsecure by design and could allow users to do more on the system than a regular user should be able to do, will never be supported.

So you should pull containers from a container repository, or build the container on your own workstation and then transfer it to LUMI.

There is some support for building on top of an existing singularity container using what the SingularityCE user guide

calls "unprivileged proot builds".

This requires loading the proot command which is provided by the systools module

in CrayEnv or LUMI/23.09 or later or the PRoot module. The SingularityCE user guide

mentions several restrictions of this process.

The general guideline from the manual is: "Generally, if your definition file starts from an existing SIF/OCI container image,

and adds software using system package managers, an unprivileged proot build is appropriate.

If your definition file compiles and installs large complex software from source,

you may wish to investigate --remote or --fakeroot builds instead." But as we just said,

on LUMI we cannot yet

provide --fakeroot builds due to security constraints.

We have managed to compile software from source in the container, but the installation

process through proot does come with a performance penalty. This is only when building

the container though; there is no difference when running the container.

We are also working on a number of base images to build upon, where the base images are tested with the OS kernel on LUMI (and some for ROCm are already there).

Interacting with containers¶

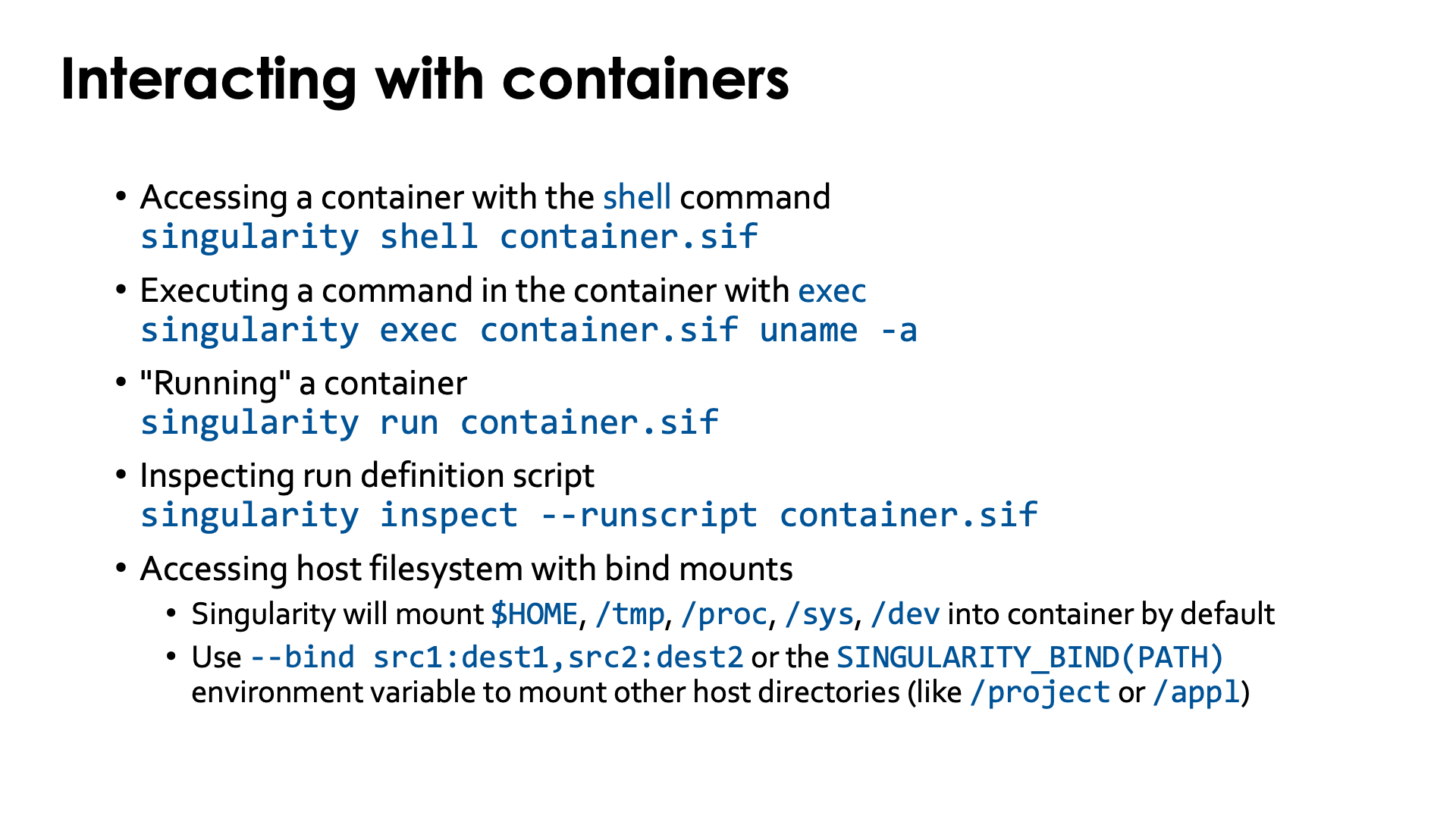

There are basically three ways to interact with containers.

If you have the sif file already on the system you can enter the container with an interactive shell:

singularity shell container.sif

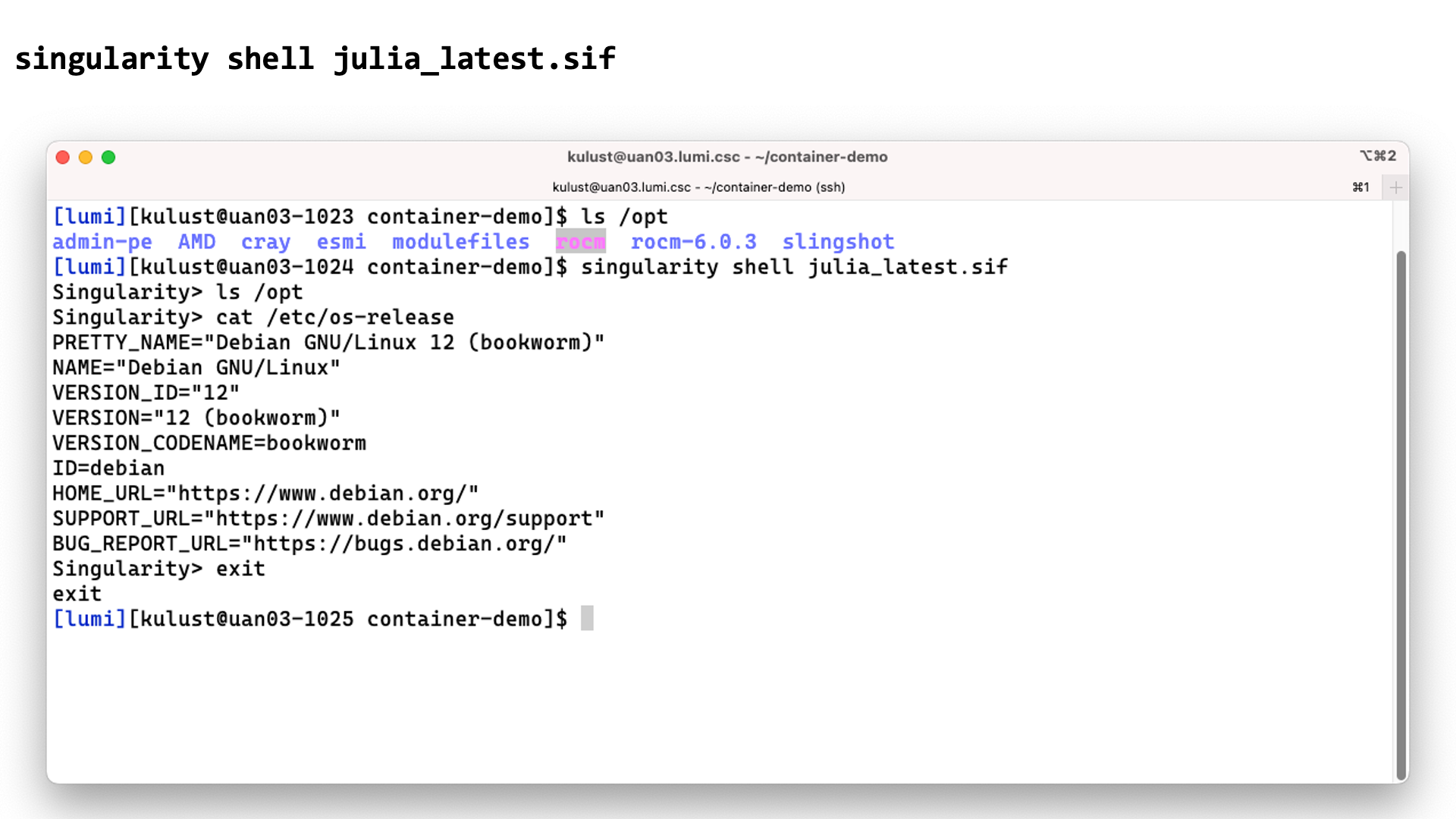

Demo singularity shell

In this screenshot we checked the contents of the /opt directory before and after the

singularity shell julia_latest.sif command. This shows that we are clearly in a different

environment. Checking the /etc/os-release file only confirms this as LUMI runs SUSE Linux

on the login nodes, not a version of Debian.

The second way is to execute a command in the container with singularity exec. E.g., assuming the

container has the uname executable installed in it,

singularity exec container.sif uname -a

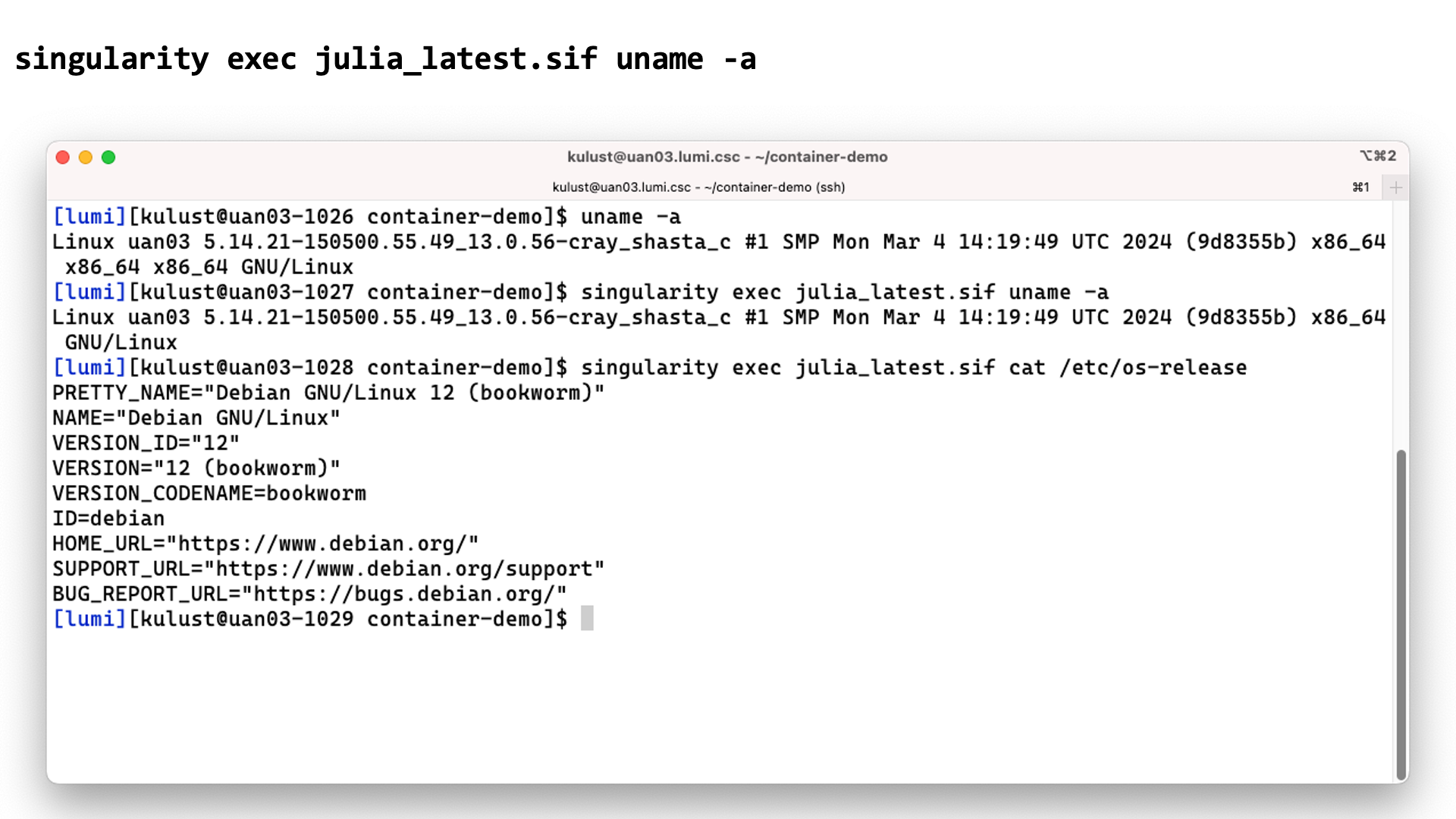

Demo singularity exec

In this screenshot we execute the uname -a command before and with the

singularity exec julia_latest.sif command. There are some slight differences in the

output though the same kernel version is reported as the container uses the host kernel.

Executing

singularity exec julia_latest.sif cat /etc/os-release

confirms though that the commands are executed in the container.

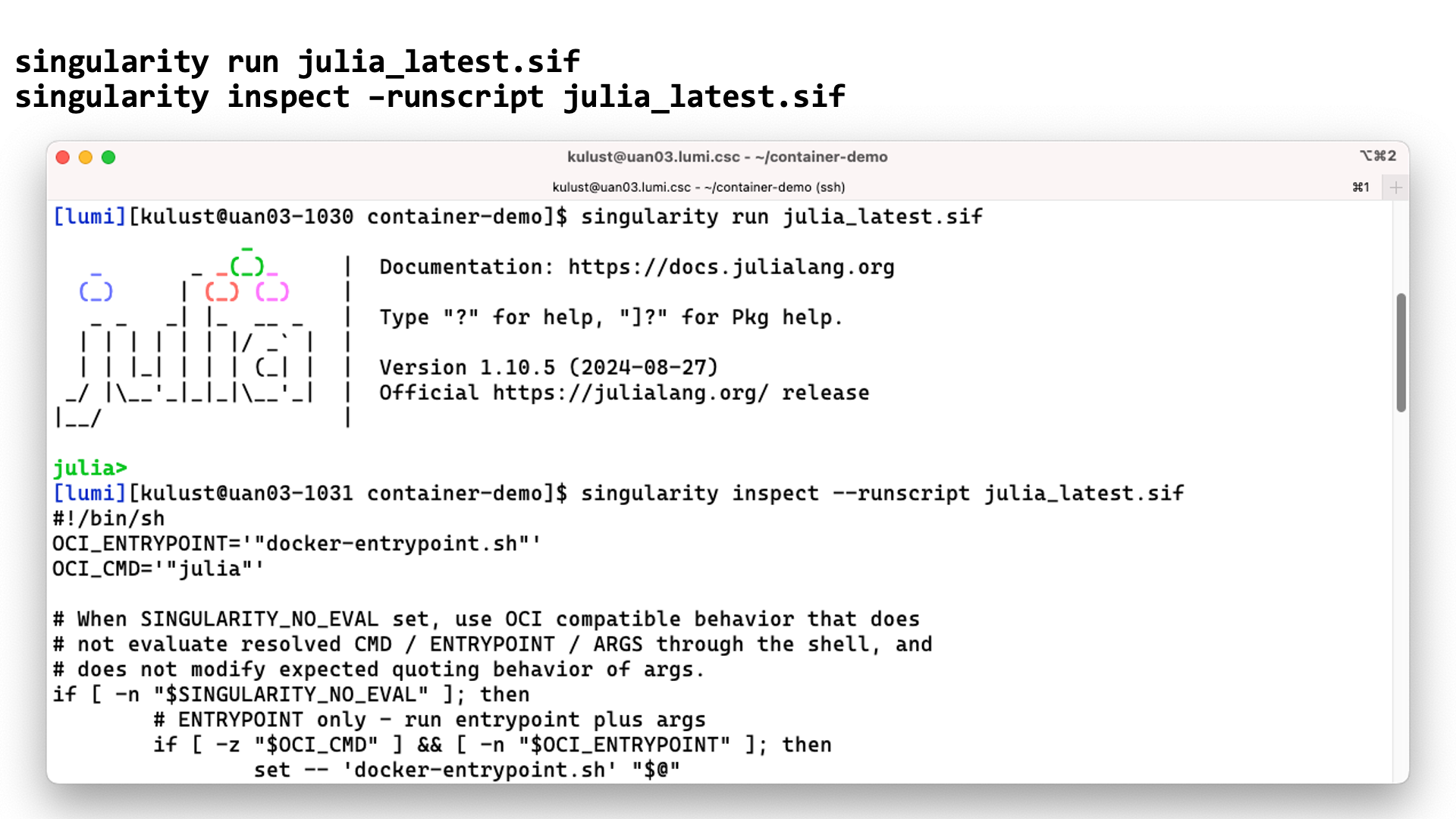

The third option is often called running a container, which is done with singularity run:

singularity run container.sif

It does require the container to have a special script that tells singularity what

running a container means. You can check if it is present and what it does with singularity inspect:

singularity inspect --runscript container.sif

Demo singularity run

In this screenshot we start the julia interface in the container using

singularity run. The second command shows that the container indeed

includes a script to tell singularity what singularity run should do.

You want your container to be able to interact with the files in your account on the system.

Singularity will automatically mount $HOME, /tmp, /proc, /sys and /dev in the container,

but this is not enough as your home directory on LUMI is small and only meant to be used for

storing program settings, etc., and not as your main work directory. (And it is also not billed

and therefore no extension is allowed.) Most of the time you want to be able to access files in

your project directories in /project, /scratch or /flash, or maybe even in /appl.

To do this you need to tell singularity to also mount these directories in the container,

either using the

--bind src1:dest1,src2:dest2

flag (or -B) or via the SINGULARITY_BIND or SINGULARITY_BINDPATH environment variables.

E.g.,

export SINGULARITY_BIND='/pfs,/scratch,/projappl,/project,/flash'

will ensure that you have access to the scratch, project and flash directories of your project.

For some containers that are provided by the LUMI User Support Team, modules are also available that

set SINGULARITY_BINDPATH so that all necessary system libraries are available in the container and

users can access all their files using the same paths as outside the container.

Running containers on LUMI¶

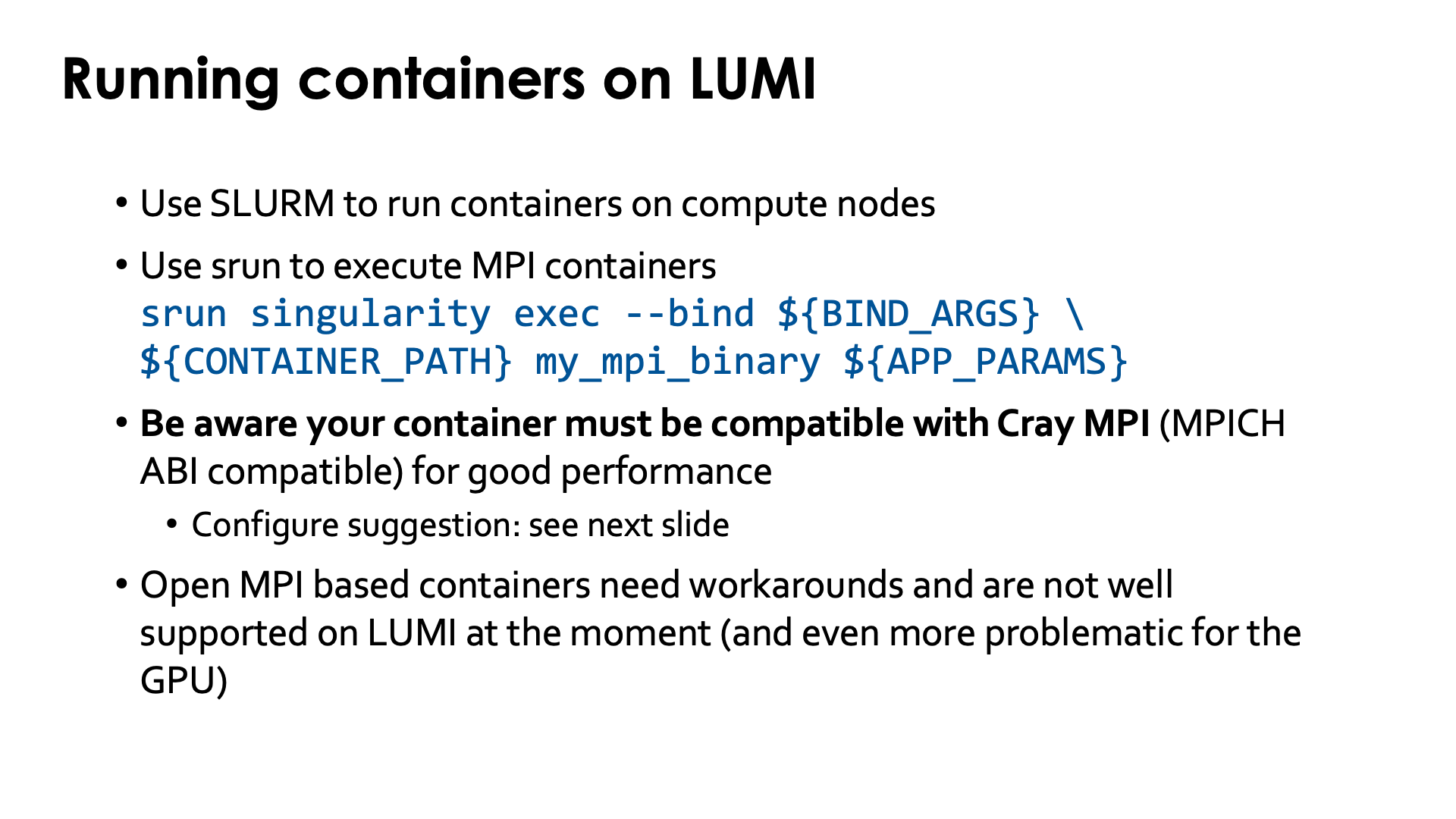

Just as for other jobs, you need to use Slurm to run containers on the compute nodes.

For MPI containers one should use srun to run the singularity exec command, e.g,,

srun singularity exec --bind ${BIND_ARGS} \

${CONTAINER_PATH} mp_mpi_binary ${APP_PARAMS}

(and replace the environment variables above with the proper bind arguments for --bind, container file and

parameters for the command that you want to run in the container).

On LUMI, the software that you run in the container should be compatible with Cray MPICH, i.e., use the MPICH ABI (currently Cray MPICH is based on MPICH 3.4). It is then possible to tell the container to use Cray MPICH (from outside the container) rather than the MPICH variant installed in the container, so that it can offer optimal performance on the LUMI Slingshot 11 interconnect.

Open MPI containers are currently not well supported on LUMI and we do not recommend using them. We only have a partial solution for the CPU nodes that is not tested in all scenarios, and on the GPU nodes Open MPI is very problematic at the moment. This is due to some design issues in the design of Open MPI and what it expects from a network fabric library, and also to some piece of software to interact with the resource manager that recent versions of Open MPI require but that HPE only started supporting recently on Cray EX systems and that we haven't been able to fully test. Open MPI has a slight preference for the UCX communication library over the OFI libraries, and until version 5 full GPU support required UCX. Moreover, binaries using Open MPI often use the so-called rpath linking process so that it becomes a lot harder to inject an Open MPI library that is installed elsewhere. The good news though is that the Open MPI developers of course also want Open MPI to work on biggest systems in the USA, and all three currently operating or planned exascale systems use the Slingshot 11 interconnect, so work is going on for better support for OFI in general and Cray Slingshot in particular and for full GPU support.

Enhancements to the environment¶

To make life easier, LUST with the support of CSC did implement some modules that are either based on containers or help you run software with containers.

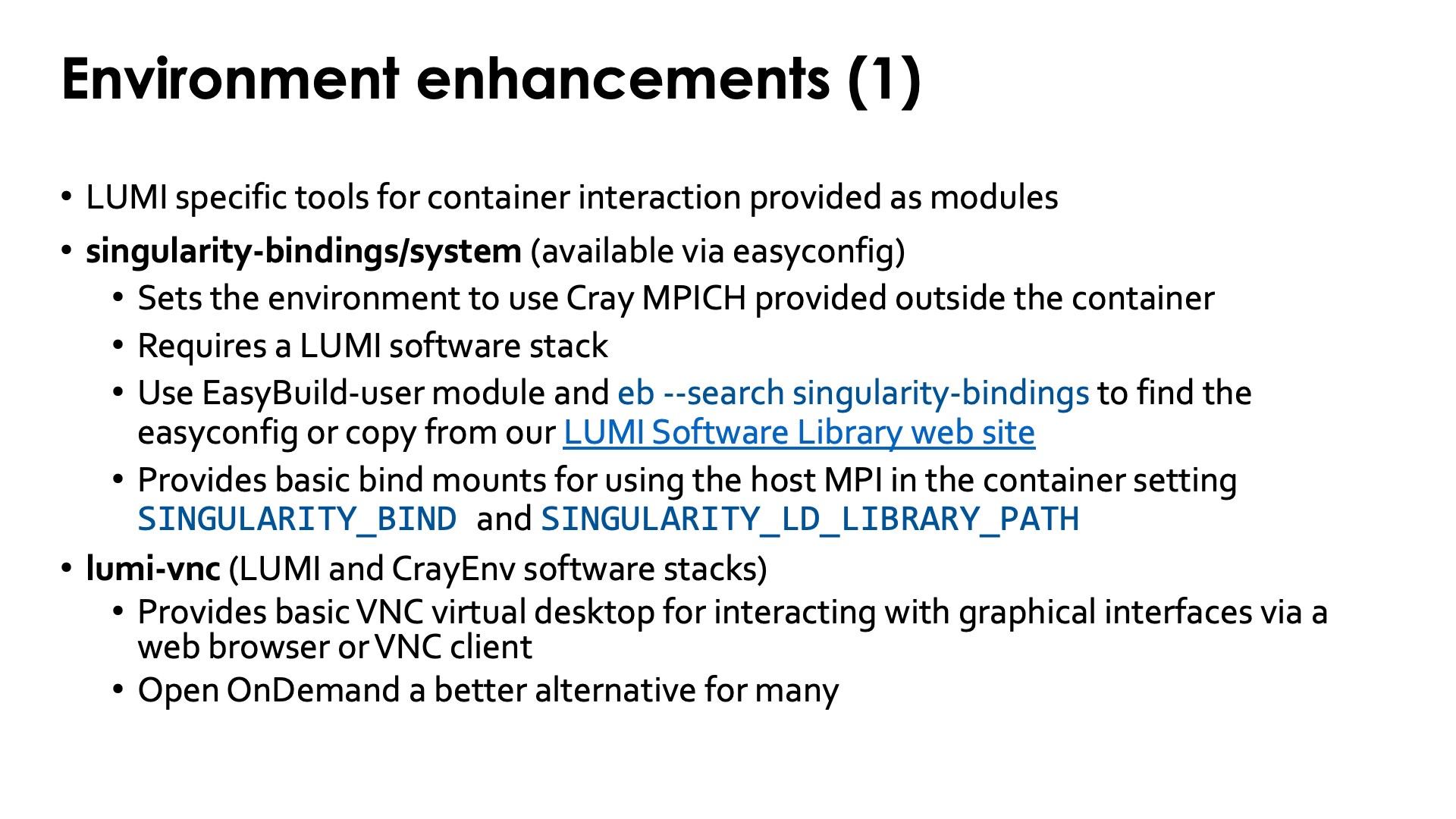

Bindings for singularity¶

singularity-bindings/system¶

The singularity-bindings/system module which can be installed via EasyBuild

helps to set SINGULARITY_BIND and SINGULARITY_LD_LIBRARY_PATH to use

Cray MPICH. Figuring out those settings is tricky, and sometimes changes to the

module are needed for a specific situation because of dependency conflicts

between Cray MPICH and other software in the container, which is why we don't

provide it in the standard software stacks but instead make it available as

an EasyBuild recipe that you can adapt to your situation and install.

As it needs to be installed through EasyBuild, it is really meant to be

used in the context of a LUMI software stack (so not in CrayEnv).

To find the EasyConfig files, load the EasyBuild-user module and

run

eb --search singularity-bindings

You can also check the

page for the singularity-bindings in the LUMI Software Library.

You may need to change the EasyConfig for your specific purpose though.

E.g., the singularity command line option --rocm to import the ROCm installation

from the system doesn't fully work (and in fact, as we have alternative ROCm versions

on the system cannot work in all cases) but that can also be fixed by extending

the singularity-bindings module

(or by just manually setting the proper environment variables).

singularity-AI-bindings¶

A second module helping with bindings, is the

singularity-AI-bindings module.

It is available as an EasyConfig if you want to install it where it works best for you,

or you can access it after

module use /appl/local/containers/ai-modules

This module provides bindings to some system libraries and to the regular file systems for some of the AI containers that are provided on LUMI. The module is in no way a generic module that will also work properly for containers that you pull, e.g., from Docker!

Build tools for Conda and Python¶

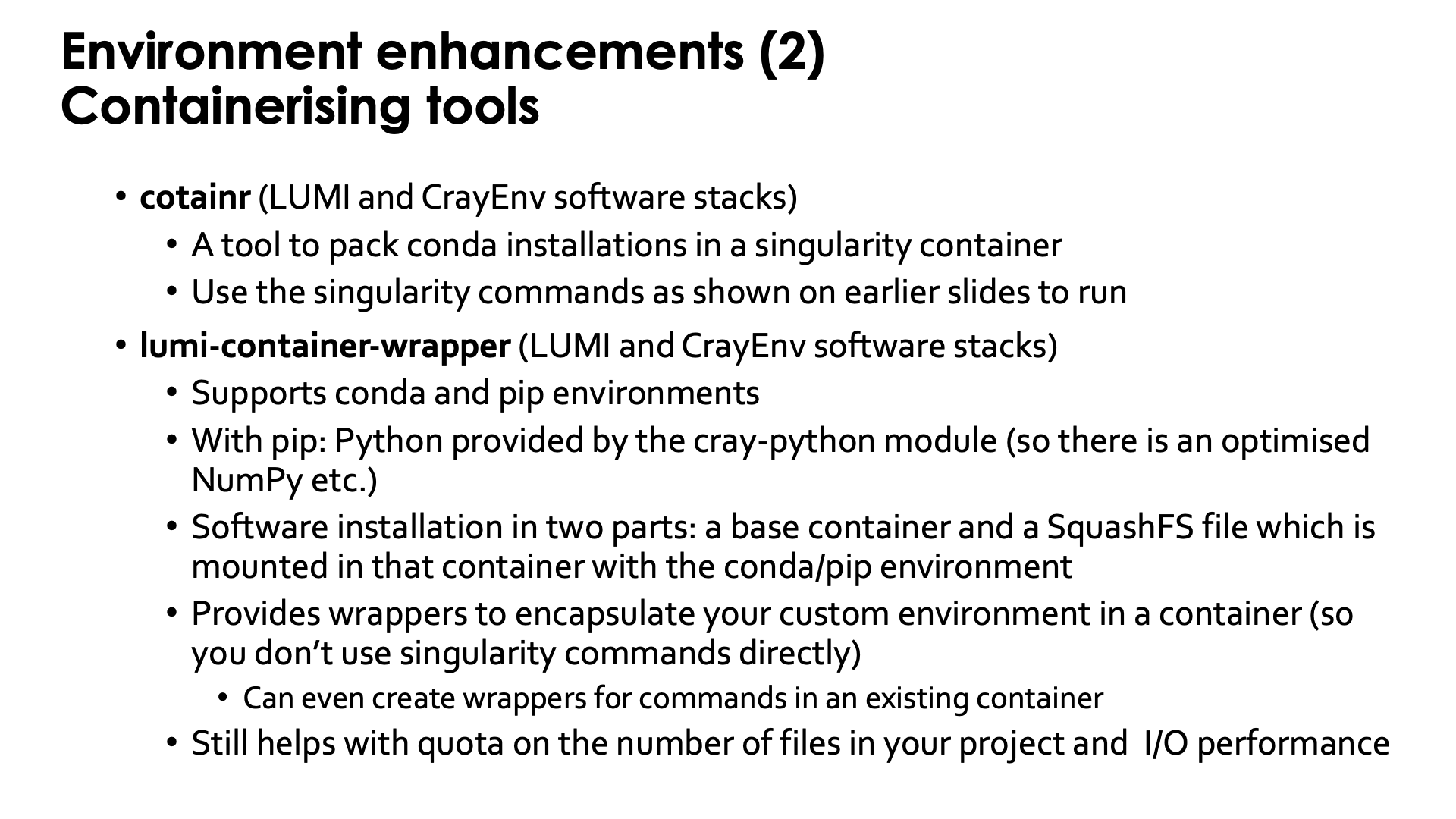

cotainr: Build Conda containers on LUMI¶

The third tool is cotainr,

a tool developed by DeIC, the Danish partner in the LUMI consortium.

It is a tool to pack a Conda installation into a container. It runs entirely in user space and doesn't need

any special rights. (For the container specialists: It is based on the container sandbox idea to build

containers in user space.)

Containers build with cotainr are used just as other containers, so through the singularity commands discussed

before.

AI course

The cotainr tool is also used extensively in the

AI workshop that the LUMI User Support Team

organises from time to time.

It is used in that course to build containers

with AI software on top of some

ROCmTM containers that we provide. A link to the course material of that training was

not yet available at the time of writing.

Container wrapper for Python packages and conda¶

The fourth tool is a container wrapper tool that users from Finland may also know

as Tykky (the name on their national systems).

It is a tool to wrap Python and conda installations in a container and then

create wrapper scripts for the commands in the bin subdirectory so that for most

practical use cases the commands can be used without directly using singularity

commands.

Whereas cotainr fully exposes the container to users and its software is accessed

through the regular singularity commands, Tykky tries to hide this complexity with

wrapper scripts that take care of all bindings and calling singularity.

On LUMI, it is provided by the lumi-container-wrapper

module which is available in the CrayEnv environment and in the LUMI software stacks.

The tool can work in four modes:

-

It can create a conda environment based on a Conda environment file and create wrapper scripts for that installation.

-

It can install a number of Python packages via

pipand create wrapper scripts. On LUMI, this is done on top of one of thecray-pythonmodules that already contain optimised versions of NumPy, SciPy and pandas. Python packages are specified in arequirements.txtfile used bypip. -

It can do a combination of both of the above: Install a Conda-based Python environment and in one go also install a number of additional Python packages via

pip. -

The fourth option is to use the container wrapper to create wrapper scripts for commands in an existing container.

For the first three options, the container wrapper will then perform the installation

in a work directory, create some wrapper commands in the bin subdirectory of the directory

where you tell the container wrapper tool to do the installation,

and it will use SquashFS to create as single file

that contains the conda or Python installation. So strictly speaking it does not create a

container, but a SquashFS file that is then mounted in a small existing base container.

However, the wrappers created for all commands in the bin subdirectory of the conda or

Python installation take care of doing the proper bindings. If you want to use the container

through singularity commands however, you'll have to do that mounting by hand, including

mounting the SquashFS file on the right directory in the container.

Note that the wrapper scripts may seem transparent, but running a script that contains the wrapper commands outside the container may have different results from running the same script inside the container. After all, the script that runs outside the container sees a different environment than the same script running inside the container.

We do strongly recommend to use cotainr or the container wrapper tool for larger conda and Python installation.

We will not raise your file quota if it is to house such installation in your /project directory.

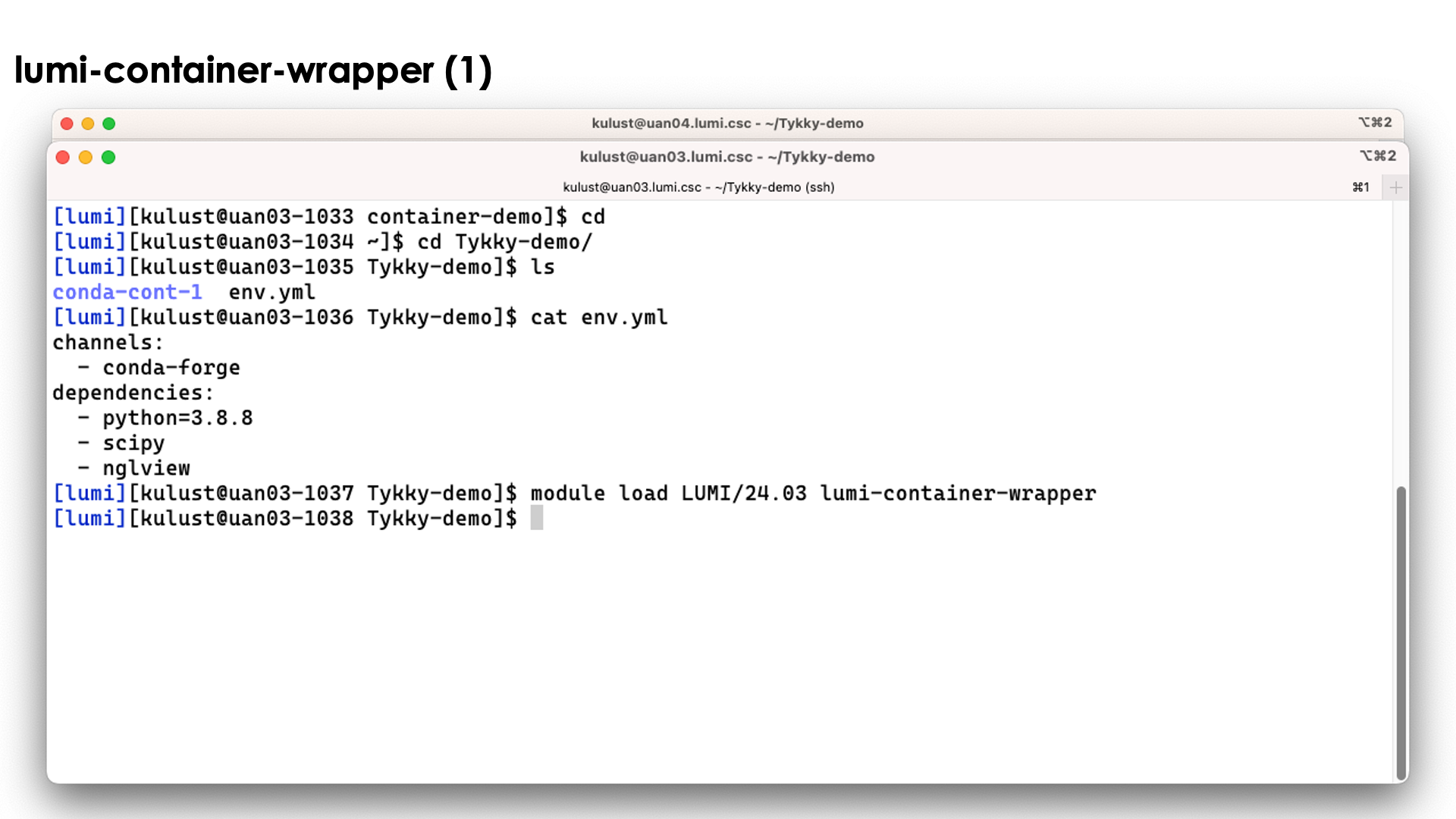

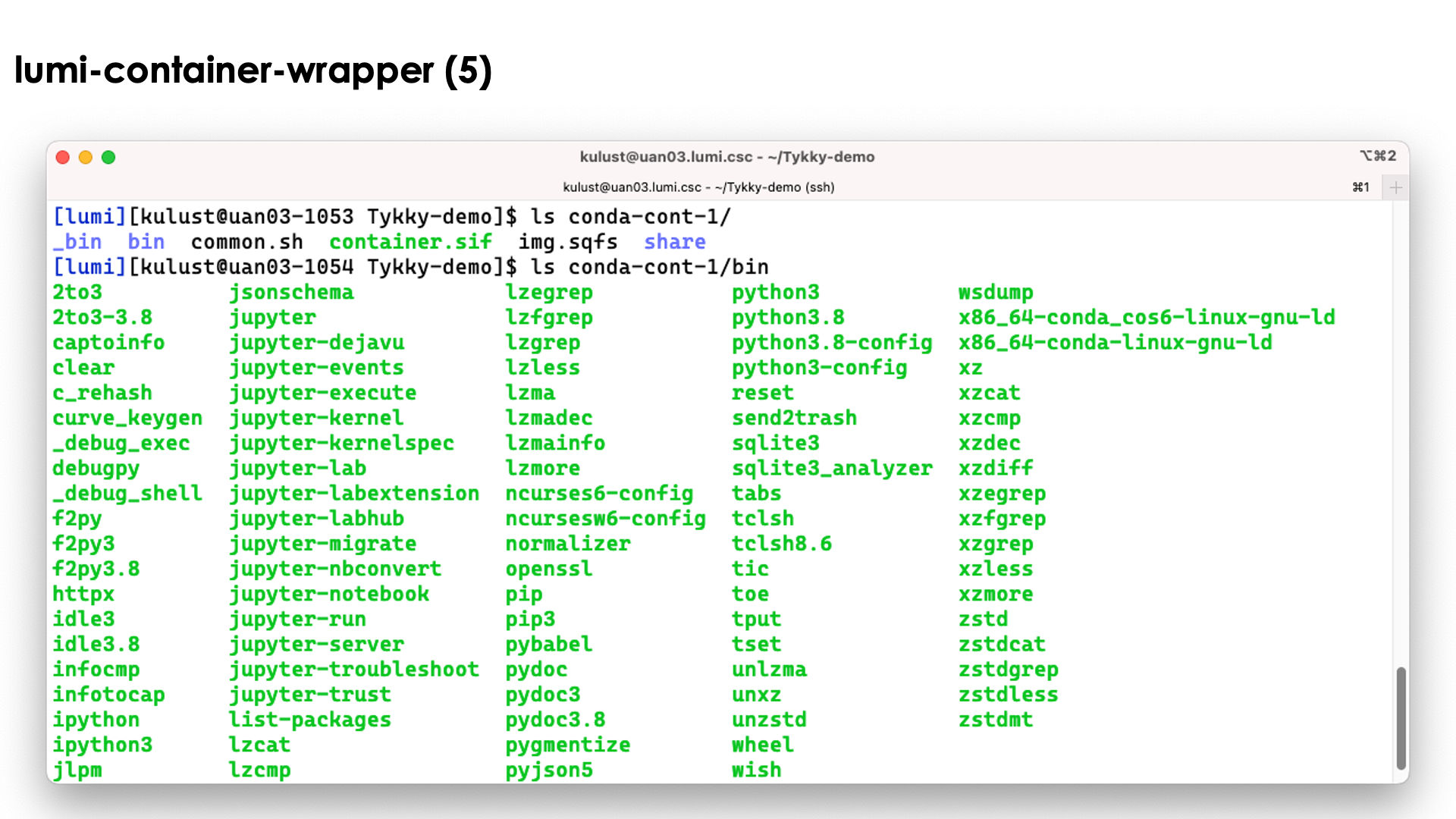

Demo lumi-container-wrapper for a Conda installation

Create a subdirectory to experiment. In that subdirectory, create a file named env.yml with

the content:

channels:

- conda-forge

dependencies:

- python=3.8.8

- scipy

- nglview

and create an empty subdirectory conda-cont-1.

Now you can follow the commands on the slides below:

On the slide above we prepared the environment.

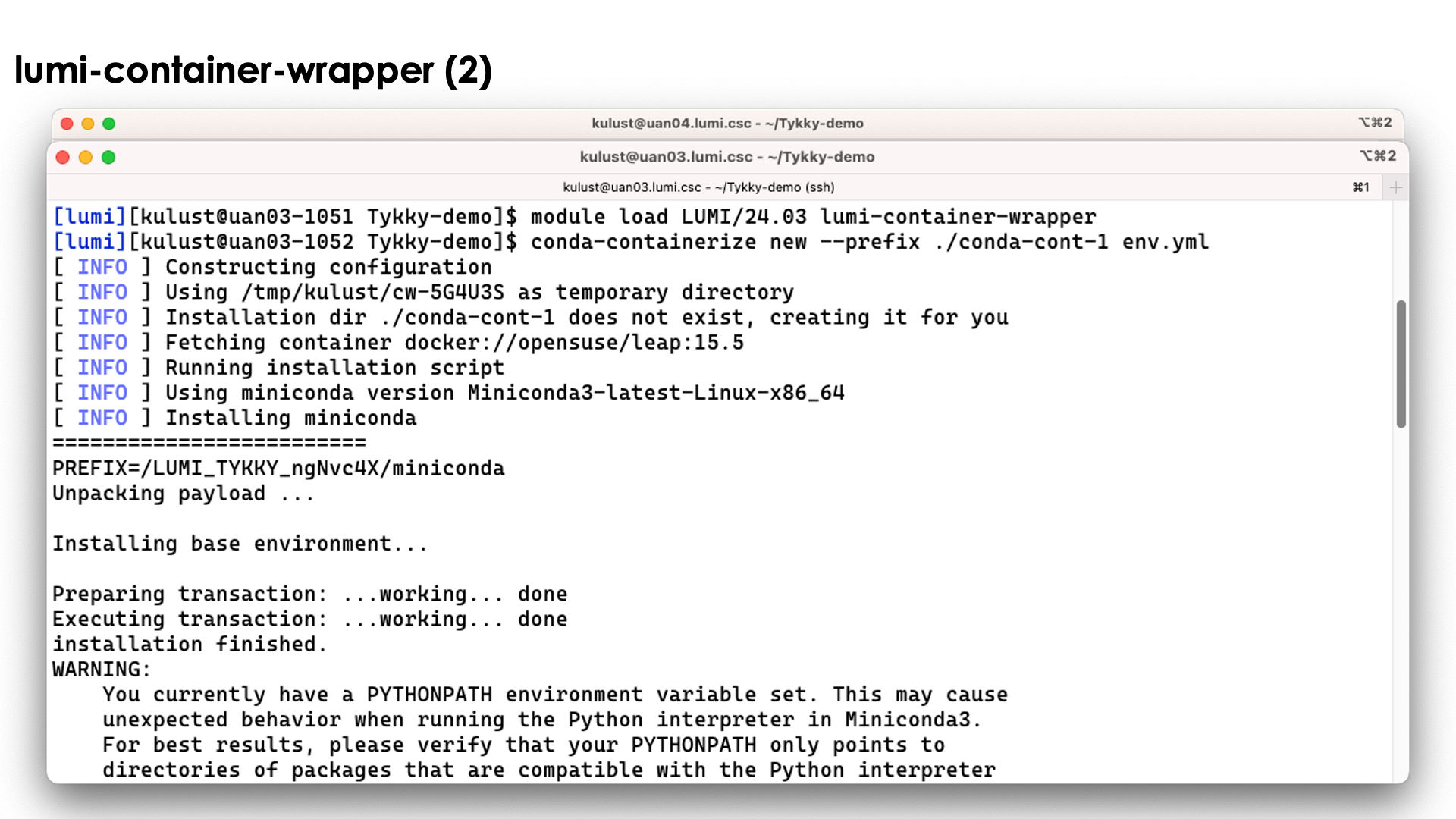

Now lets run the command

conda-containerize new --prefix ./conda-cont-1 env.yml

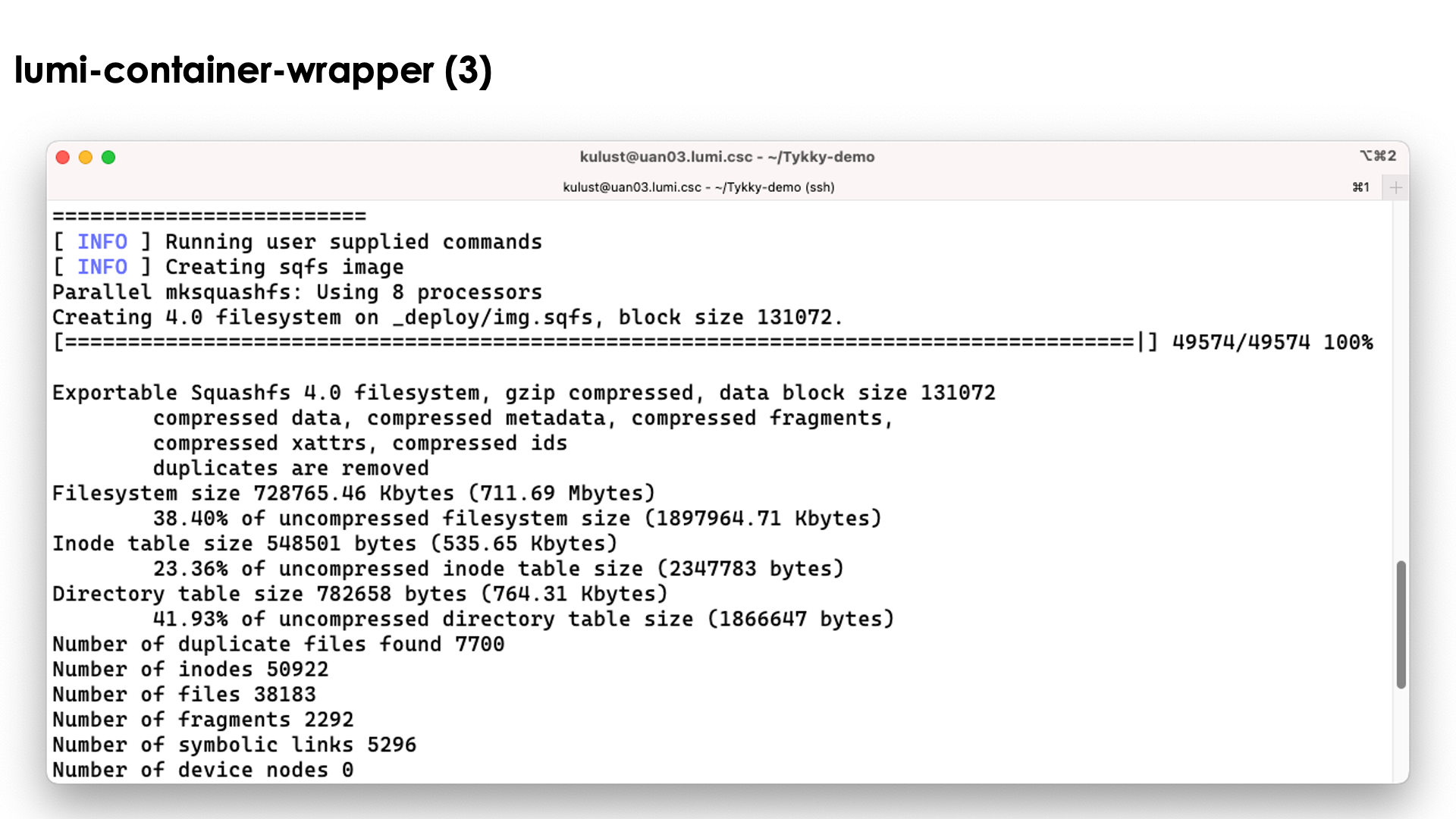

and look at the output that scrolls over the screen. The screenshots don't show the full output as some parts of the screen get overwritten during the process:

The tool will first build the conda installation in a tempororary work directory and also uses a base container for that purpose.

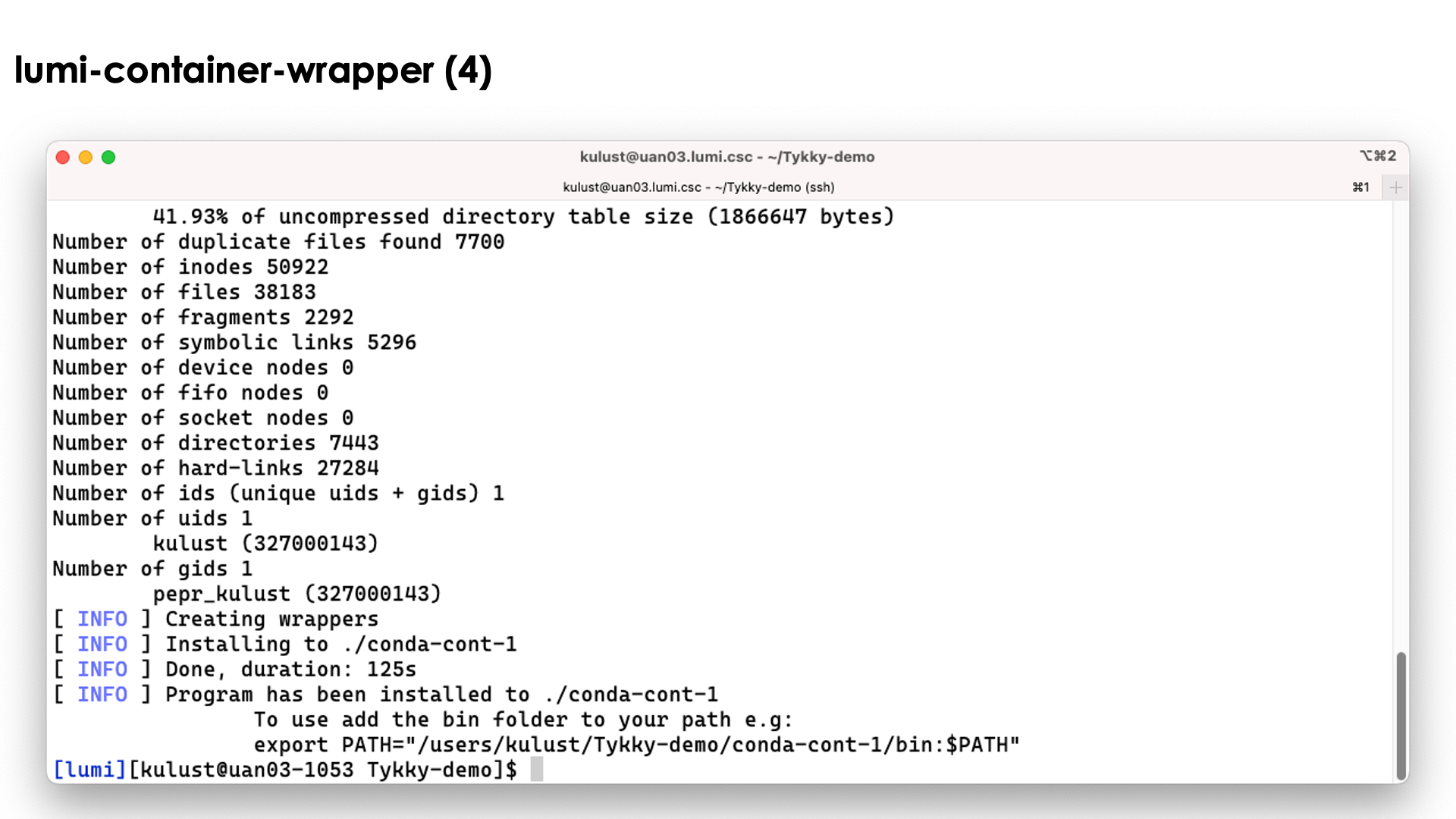

The conda installation itself though is stored in a SquashFS file that is then used by the container.

In the slide above we see the installation contains both a singularity container and a SquashFS file. They work together to get a working conda installation.

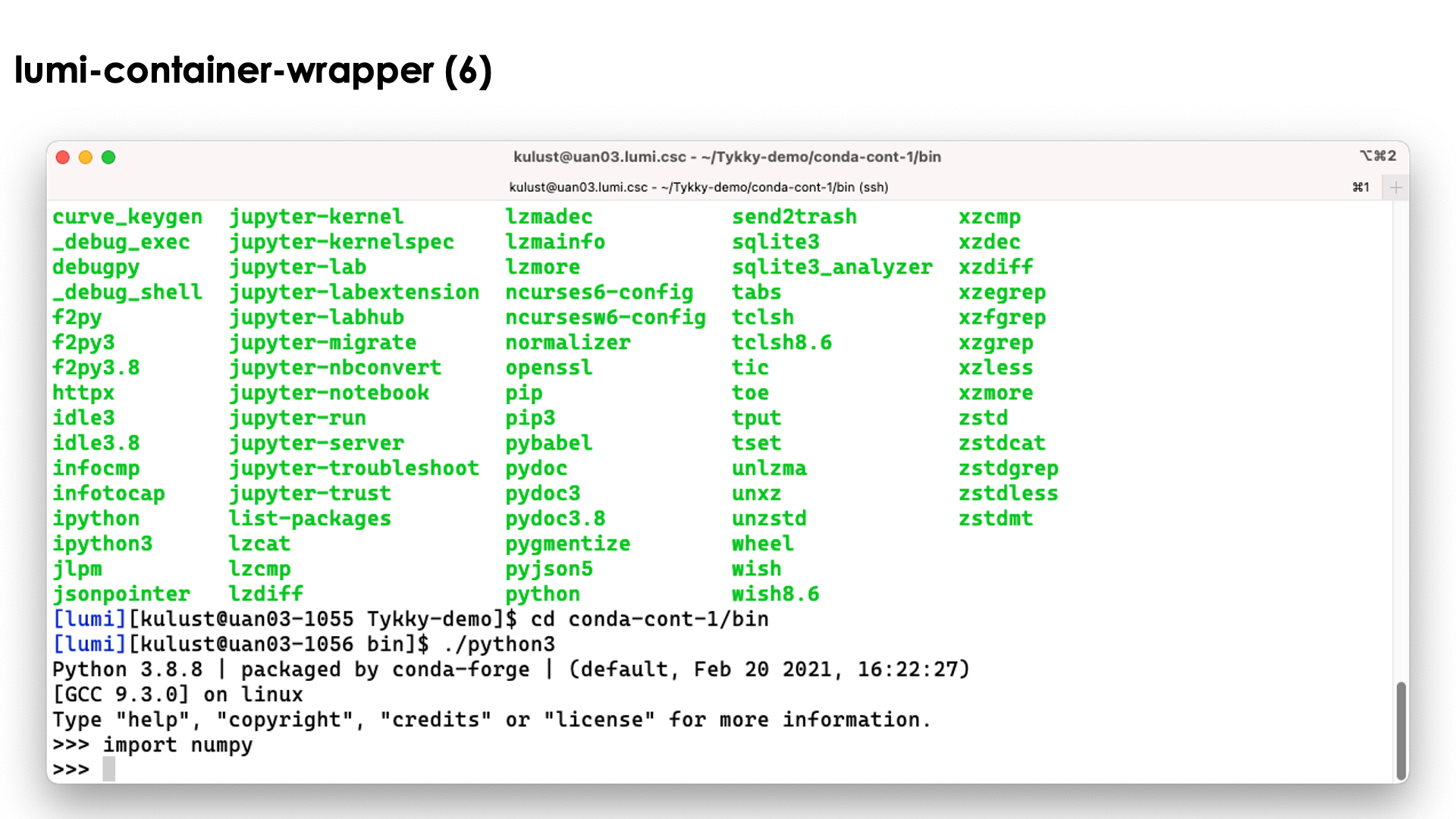

The bin directory seems to contain the commands, but these are in fact scripts

that run those commands in the container with the SquashFS file system mounted in it.

So as you can see above, we can simply use the python3 command without realising

what goes on behind the screen...

Relevant documentation for lumi-container-wrapper

Pre-build containers: VNC and CCPE¶

VNC¶

The fifth tool is a container that we provide with some bash functions

to start a VNC server as one way to run GUI programs and as an alternative to

the (currently more sophisticated) VNC-based GUI desktop setup offered in Open OnDemand

(see the "Getting Access to LUMI notes").

It can be used in CrayEnv or in the LUMI stacks through the

lumi-vnc module.

The container also

contains a poor men's window manager (and yes, we know that there are sometimes

some problems with fonts). It is possible to connect to the VNC server either

through a regular VNC client on your PC or a web browser, but in both cases you'll

have to create an ssh tunnel to access the server. Try

module help lumi-vnc

for more information on how to use lumi-vnc.

For most users, the Open OnDemand web interface and tools offered in that interface will be a better alternative.

CCPE¶

We are currently also working with HPE to provide a containerised Cray Programming Environment to be able to test newer versions of the Cray PE than are offered on LUMI.

As working in a container requires a very good understanding of the differences between the environment in and out of the container, using those containers is really only for more experienced users who understand how modules and environments work.

These containers will be offered with user-installable EasyBuild recipes (ccpe in the LUMI Software Library) as customisation for the particular purpose of the user will often be necessary. This can often be done by minor changes to the recipes provided by LUST.

The functionality of this solution may still be limited though, in particular for GPU applications. Each version of the Cray PE is developed with one or a few specific versions of ROCm™ in mind, so if that version of ROCm™ is too new for the current driver on the software, running GPU software may fail. Some containers may also expect a newer version of the OS and though they contain the necessary userland libraries, these may expect a newer version of the kernel or libraries that are injected from the system.

User coffee break seminar on the CCPE containers

During the August 2025 LUMI user coffee break, there was a presentation on using the Cray PE containers.

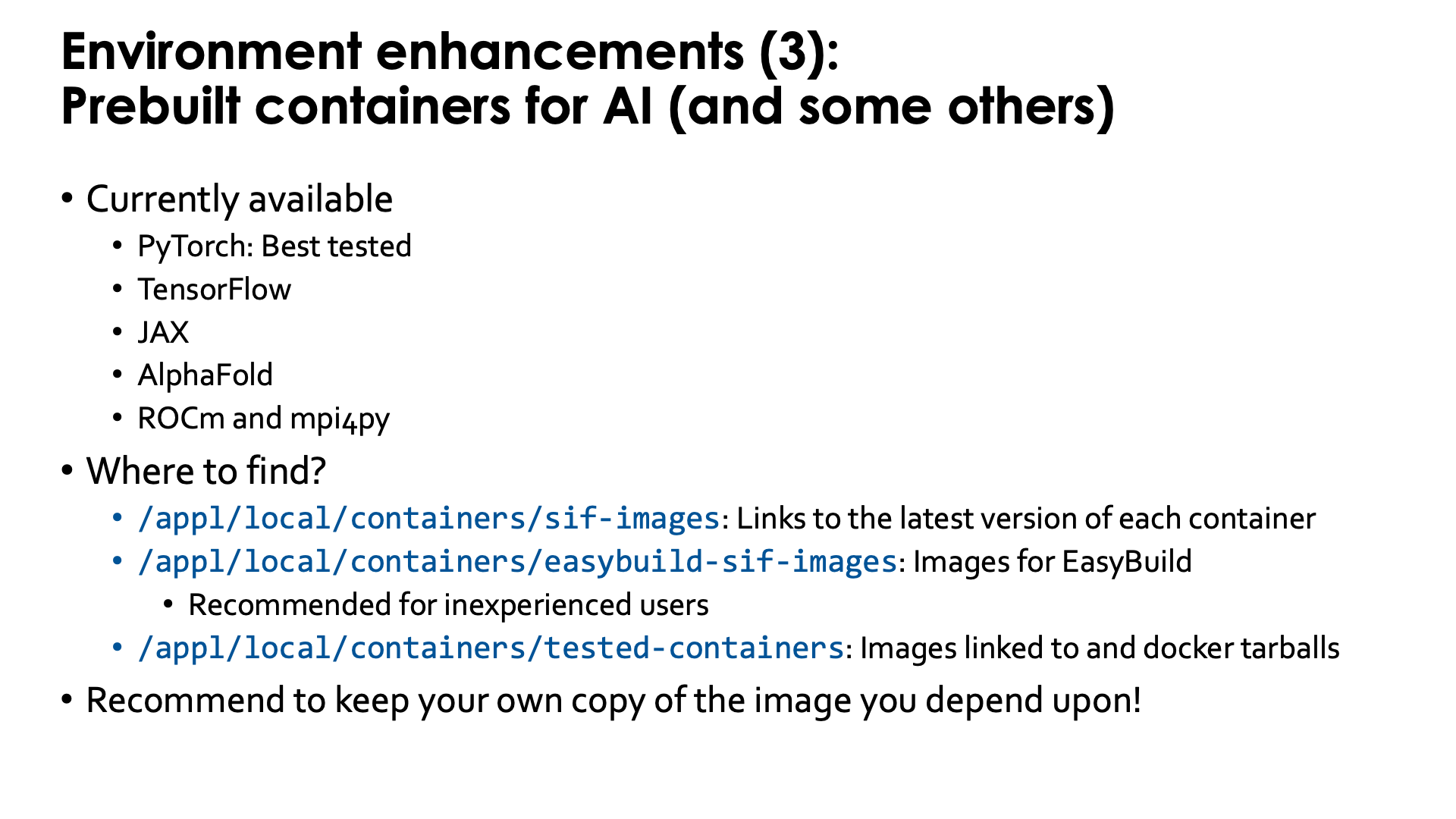

Pre-built AI containers¶

LUST with the help of AMD is also building some containers with popular AI software. These containers contain a ROCm version that is appropriate for the software, use Conda for some components, but have several of the performance critical components built specifically for LUMI for near-optimal performance. Depending on the software they also contain a RCCL library with the appropriate plugin to work well on the Slingshot 11 interconnect, or a horovod compiled to use Cray MPICH.

Some of the containers can be provided through a module that is user-installable with EasyBuild.

That module sets the SINGULARITY_BIND environment variable

to ensure proper bindings (as some need, e.g., the libfabric library from the system and the proper

"CXI provider" for libfabric to connect to the Slingshot interconnect). The module will also provide

an environment variable to refer to the container (name with full path) to make it easy to refer to

the container in job scripts. Some of the modules also provide some scripts that may make using the containers easier in some standard scenarios.

Alternatively, the user support team also provides the singularity-AI-bindings module discussed above,

for users who want to run the containers as manually as possible yet want an

easy way to deal with the necessary bindings of user file systems and HPE Cray PE components needed

from the system (see also course materials for the AI training/workshop).

These containers can be found through the LUMI Software Library and are marked with a container label. At the time of the course, there are containers for

- PyTorch, which is the best tested and most developed one,

- JAX,

- TensorFlow,

- AlphaFold,

- ROCm and

- mpi4py.

Of these, the PyTorch containers are by far the most popular ones among the LUMI users,

probably followed by the ROCm containers as basis to build their own containers using

cotainr or other tools.

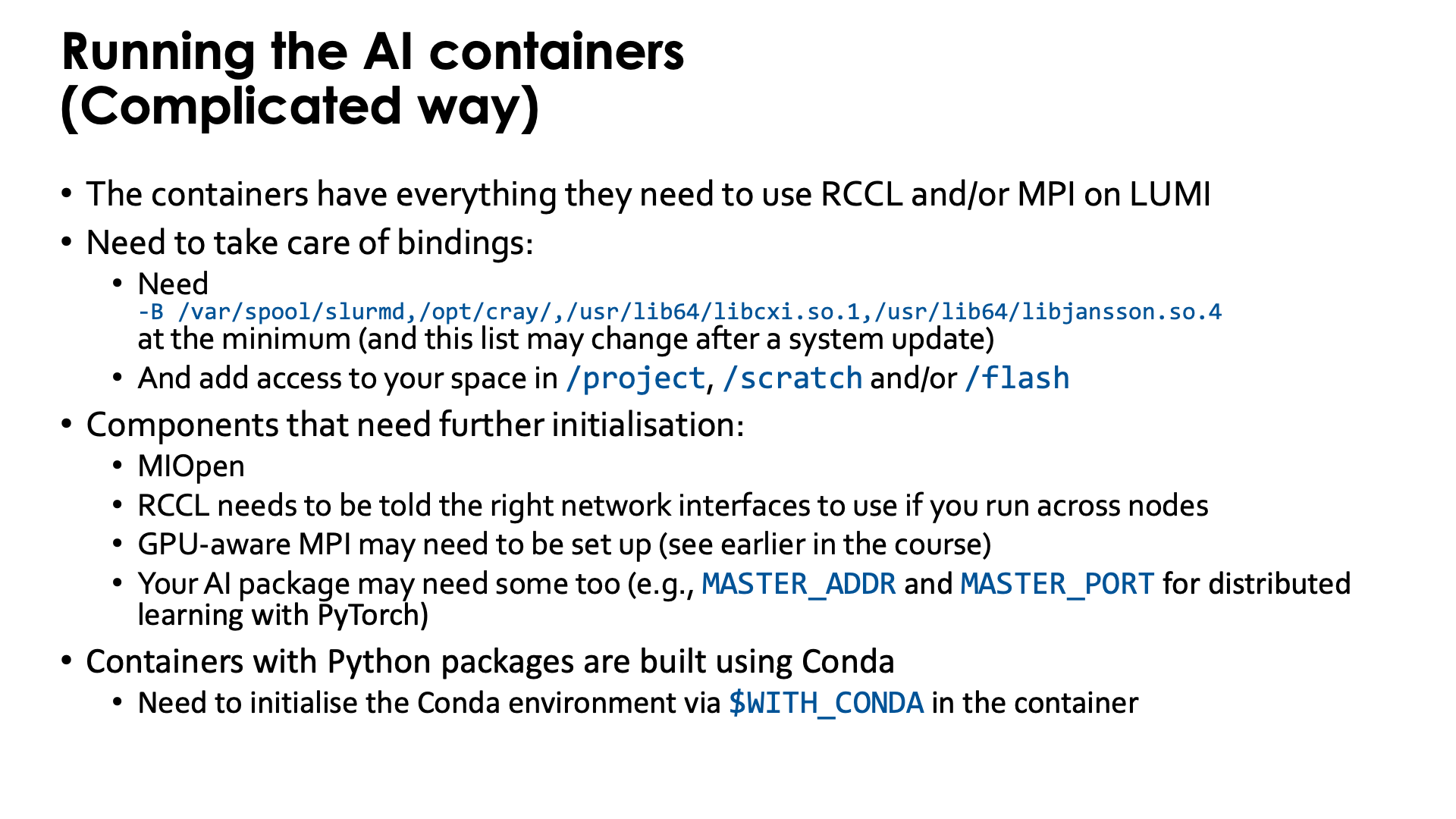

Running the AI containers - complicated way without modules¶

The containers that we provide have everything needed to use RCCL and/or MPI on LUMI.

It is not needed to use the singularity-bindings/system module described earlier as that module

tries to bind too much external software to the container.

Yet to be able to properly use the containers, users do need to take care of some bindings

-

Some system directories and libraries have to be bound to the container:

-B /var/spool/slurmd,/opt/cray,/usr/lib64/libcxi.so.1The first one is needed to work together with Slurm. The second one contains the MPI and libfabric library. The third one is the actual component that binds libfabric to the Slingshot network adapter and is called the CXI provider and is not needed anymore on the containers built in 2025 as a newer provider library has already been included in those containers.

-

By default your home directory will be available in the container, but as your home directory is not your main workspace, you may want to bind your subdirectory in

/project,/scratchand/or/flashalso, using, e.g.,-B /pfs,/scratch,/projappl,/project,/flash

There are also a number of components that may need further initialisation:

-

The MIOpen library (which is the equivalent of the CUDA cuDNN library) has problems with file/record locking on Lustre so some environment variables are needed to move some work directories to

/tmp. -

RCCL (the ROCm™ equivalent of the NVIDIA NCCL communication library) needs to be told the right network interfaces to use as otherwise it tends to take the interface to the management network of the cluster instead and gets stuck.

-

GPU-aware MPI also needs to be set up (see earlier in the course)

-

Your AI package may need some environment variables too (e.g.,

MASTER_ADDRandMASTER_PORTfor distributed learning with PyTorch)

Moreover, most (if not all at the moment) containers that we provide with Python packages, are

built using Conda to install Python. When entering those containers, conda needs to be activated.

In the newer containers (including all those built in 2025), this is done automatically in

the singularity initialisation process.

Older containers are built in such a way that the environment variable WITH_CONDA provides the

necessary command, so in most cases you only need to run

$WITH_CONDA

as a command in the script that is executed in the container or on the command line. (And in fact, using this in the newer containers will not cause an error or warning.)

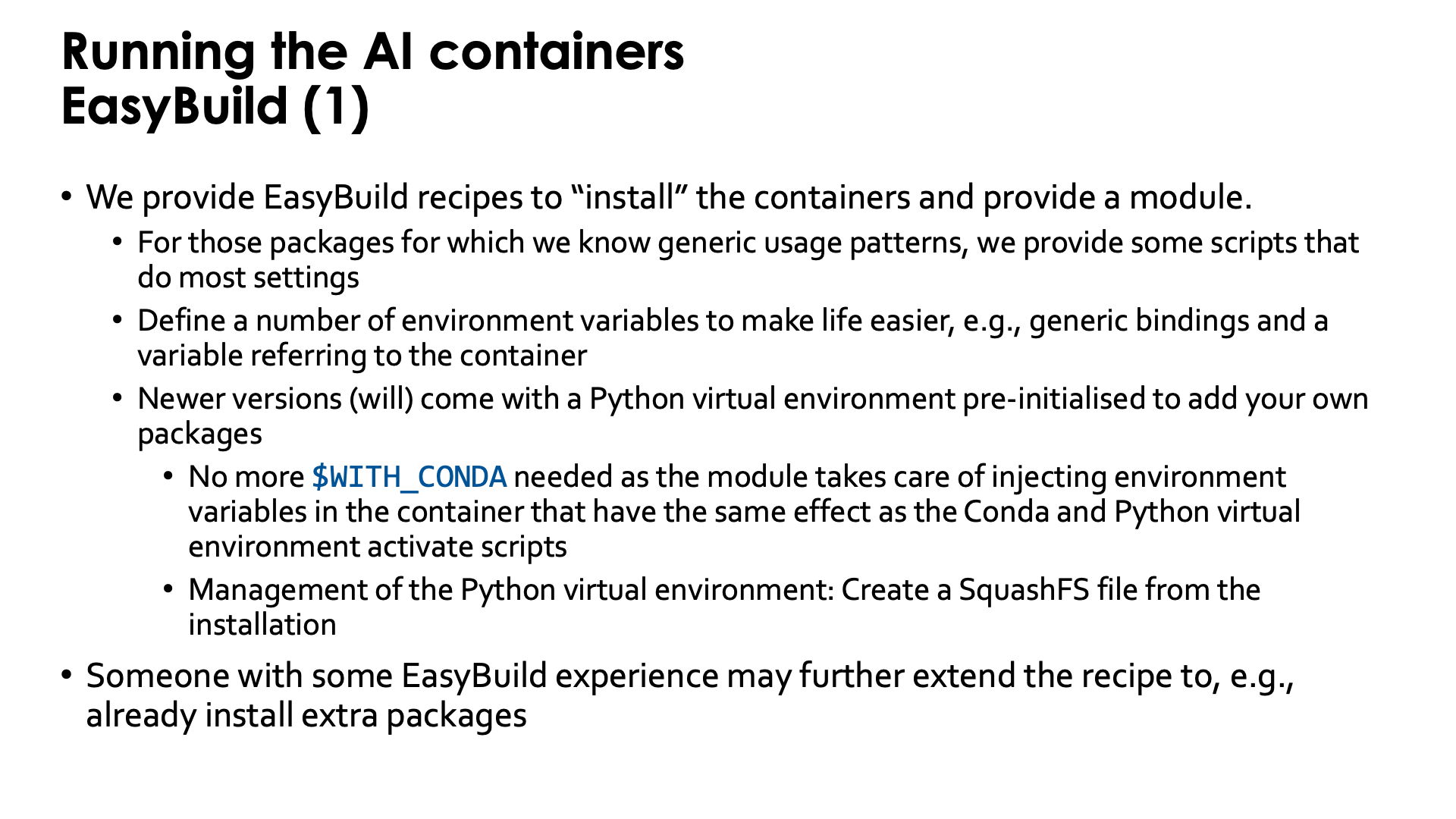

Running the containers through EasyBuild-generated modules¶

Doing all those initialisations, is a burden. Therefore we provide EasyBuild recipes to "install" the containers and to provide a module that helps setting environment variables in the initialisation.

For packages for which we know generic usage patterns, we provide some scripts that do most settings.

We may have to drop that though, as sometimes there are simply too many scenarios and promoting a particular

one too much may mislead users and encourage them to try to map their problem on an approach which

may be less efficient than theirs.

When using the module, those scripts will be available in the /runscripts directory in the container,

but are also in a subdirectory on the Lustre file system. So in principle you can even edit them or

add your own scripts, though they would be erased if you reinstall the module with EasyBuild.

Some of the newer PyTorch containers (from PyTorch 2.6.0 on) also provide wrapper scripts similar to

the wrapper scripts provided by the CSC pytorch modules,

so many of the examples in their documentation should also work with minimal changes (such as the

module name).

The modules also define a number of environment variables that make life easier. E.g., the SINGULARITY_BINDPATH

environment variable is already set to bind the necessary files and directories from the system and to

make sure that your project, scratch and flash spaces are available at the same location as on LUMI so

that even symbolic links in those directories should still work.

We recently started adding a pre-configured virtual environment to the containers to add your own packages.

The virtual environment can be found in the container in a subdirectory of /user-software/venv. To install

packages from within the container, this directory needs to be writeable which is done by binding /user-software to the

$CONTAINERROOT/user-software subdirectory outside the container.

If you add a lot of packages that way, you re-create the filesystem issues that the container is supposed to

solve, but we have a solution for that also. These containers provide the make-squashfs command to generate

a SquashFS file from the installation that will be used by the container instead next time the module for

the container is reloaded. And in case you prefer to fully delete the user-software subdirectory afterwards

from $CONTAINERROOT, it can be re-created using unmake-squashfs so that you can add further packages.

You can also use /user-software to install software in other ways from within the container and can

basically create whatever subdirectory you want into it.

This is basically automating the procedure described

in the "Extending containers with virtual environments for faster testing" lecture of the

AI training provided by the LUMI User Support Team.

These containers with pre-configured virtual environment offer another advantage also: The module injects a number of environment variables into the container so that it is no longer needed to activate the conda environment and Python virtual environment by sourcing scripts.

In fact, someone with EasyBuild experience may even help you to further extend the recipe that we provide to already install extra packages, and we provide an example of how to do that with our PyTorch containers.

Difference between the Python wrapper scrips of the EasyBuild and the CSC modules

The wrapper scripts of the CSC modules are written in such a way that even creating virtual environments with them is supported.

This is not the case with the modules provided via EasyBuild and discussed in the

LUMI Software Library.

The newer PyTorch

and JAX

EasyBuild recipes will install modules that support the python wrapper script, but

there is a single virtual environment already pre-defined and the script will run in

that virtual environment. Because of that restriction, we can easily pack the whole

virtual environment in a SquashFS file for more efficient and Lustre-friendly

execution, which is hard or impossible to do with the CSC wrappers.

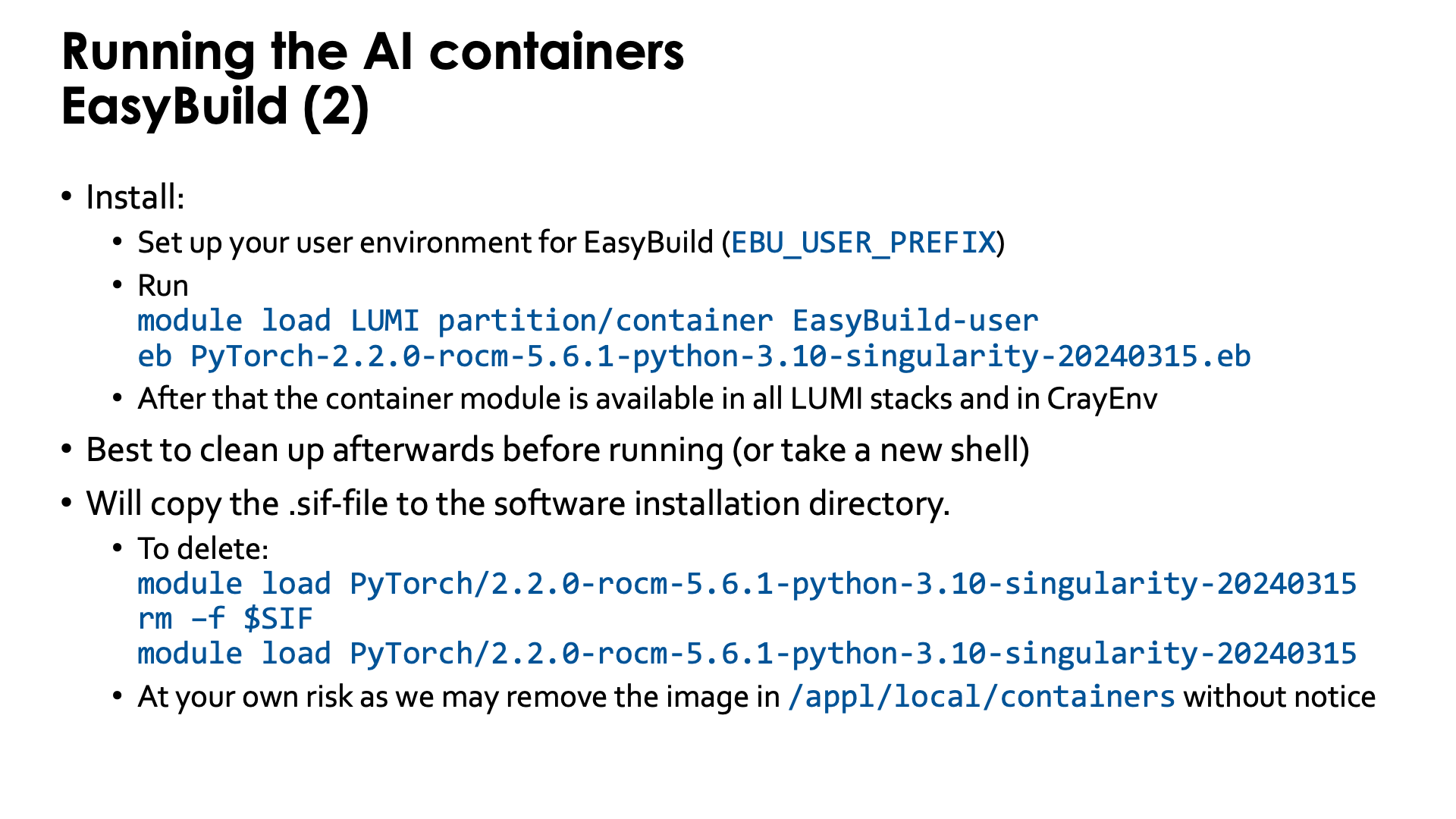

Installing the EasyBuild recipes for those containers is also done via the EasyBuild-user module,

but it is best to use a special trick. There is a special partition called partition/container that is

only used to install those containers and when using that partition for the installation, the container

will be available in all versions of the LUMI stack and in the CrayEnv stack.

Installation is as simple as, e.g.,

module load LUMI partition/container EasyBuild-user

eb PyTorch-2.6.0-rocm-6.2.4-python-3.12-singularity-20250404.eb

Before running it is best to clean up (module purge) or take a new shell to avoid conflicts with

environment variables provided by other modules.

The installation with EasyBuild will make a copy from the .sif Singularity container image file

that we provide somewhere in /appl/local/containers

to the software installation subdirectory of your $EBU_USER_PREFIX EasyBuild installation directory.

These files are big and you may wish to delete that file which is easily done: After loading the container

module, the environment variable SIF contains the name with full path of the container file.

After removing the container file from your personal software directory, you need to reload the container

module and from then on, SIF will point to the corresponding container in

/appl/local/containers/easybuild-sif-images.

So:

module load PyTorch/2.6.0-rocm-6.2.4-python-3.12-singularity-20250404

rm –f $SIF

module load PyTorch/2.6.0-rocm-6.2.4-python-3.12-singularity-20250404

We don't really recommend removing the container image though and certainly not if you are interested

in reproducibility. We may remove the image in /appl/local/containers/easybuild-sif-images

without prior notice if we notice that the container has too many problems, e.g., after a system

update. But that same container that doesn't work well for others, may work well enough for you that

you don't want to rebuild whatever environment you built with the container.

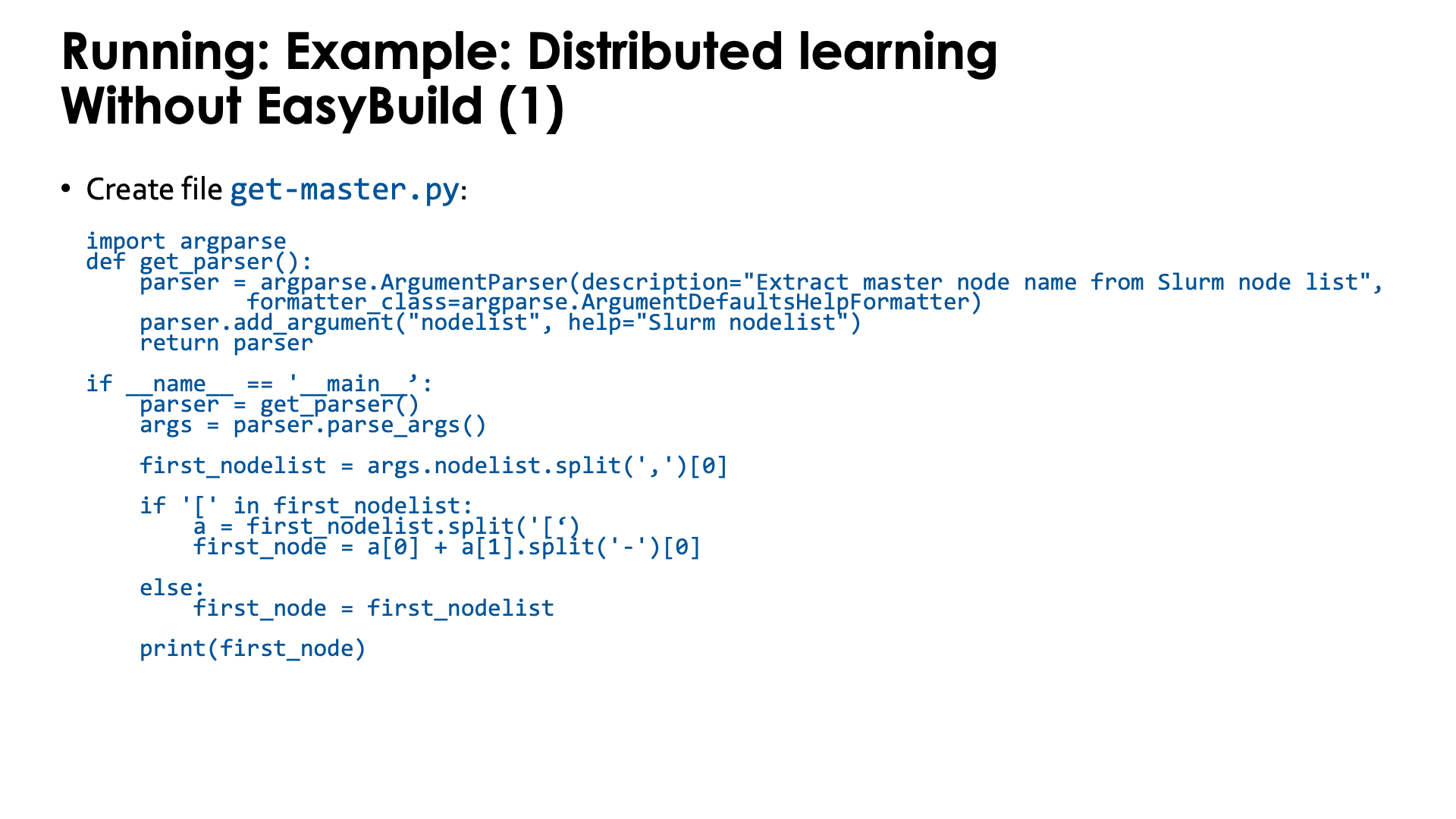

Example: Distributed learning without using EasyBuild¶

To really run this example, some additional program files and data files are needed that are not explained in this text. You can find more information on the PyTorch page in the LUMI Software Library.

In this example, we'll do most of the initialisations inside the container, but different approaches are also possible.

We'll need to create a number of scripts before we can even run the container. The job script alone is not enough as there are also per-task initialisations needed that cannot be done directly in the job script. In this example, we run the script that does the per-task initialisations in the container, but it is also possible to do this outside the container which would give access to the Slurm commands and may even simplify a bit.

If you want to know more about running AI loads on LUMI, we strongly recommend to take a look at the course materials of the AI course. Basically, running AI on AMD GPUs is not that different from NIVIDA GPUs, but there are some initialisations that are different. The main difference may be the difference between cloud environments, clusters with easy access to the compute nodes and clusters like LUMI that require you to always go through the resource manager if you want access to a compute node. We'll need to create a number of scripts before we can even run the container.

The first script is a Python program to extract the name of the master node from a Slurm environment

variable. This will be needed to set up the communication in PyTorch. Store it in get-master.py:

import argparse

def get_parser():

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description="Extract master node name from Slurm node list",

formatter_class=argparse.ArgumentDefaultsHelpFormatter)

parser.add_argument("nodelist", help="Slurm nodelist")

return parser

if __name__ == '__main__':

parser = get_parser()

args = parser.parse_args()

first_nodelist = args.nodelist.split(',')[0]

if '[' in first_nodelist:

a = first_nodelist.split('[')

first_node = a[0] + a[1].split('-')[0]

else:

first_node = first_nodelist

print(first_node)

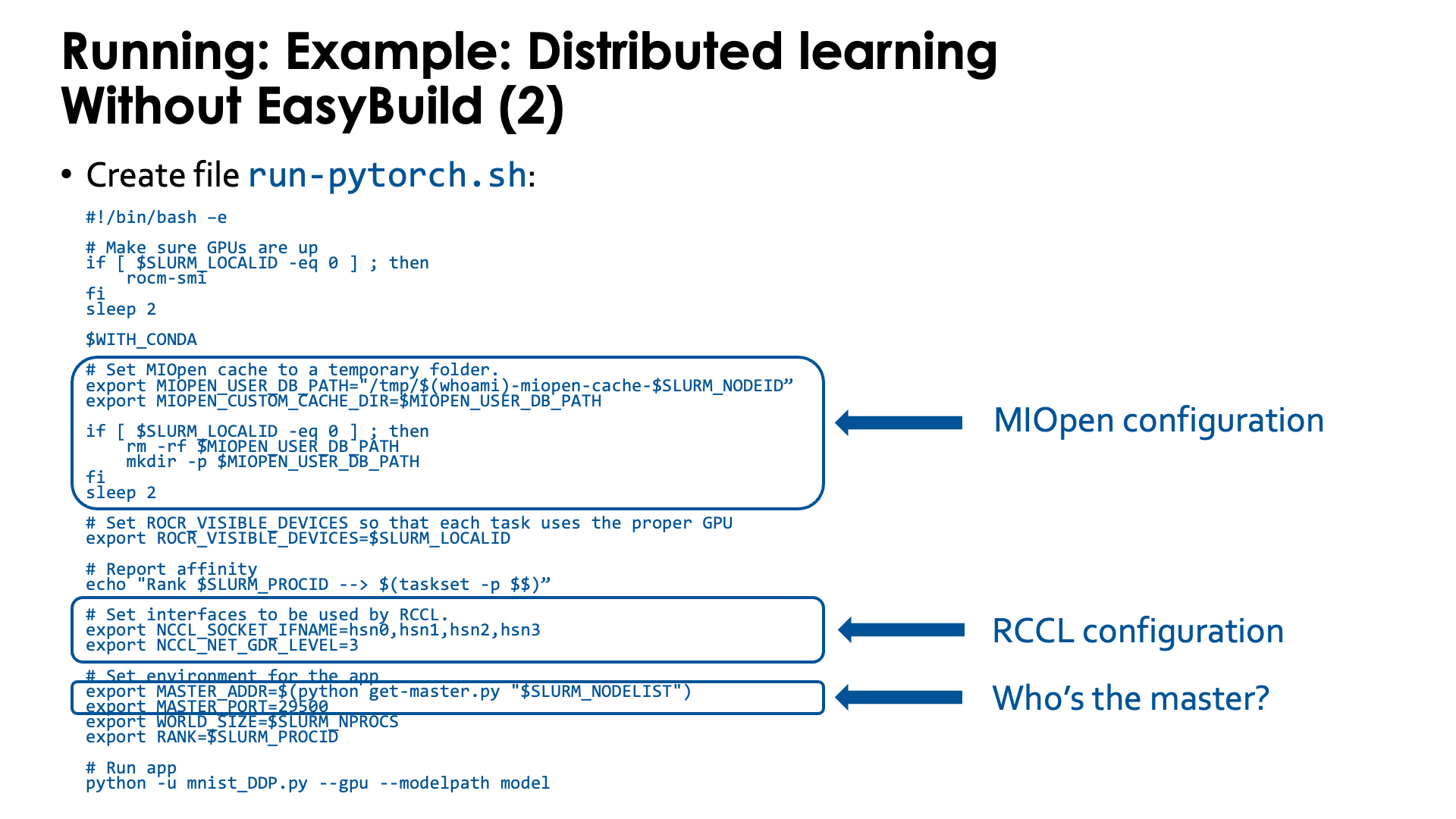

Second, we need a script that we will run in the container. Store the script as

run-pytorch.sh:

#!/bin/bash -e

# Make sure GPUs are up

if [ $SLURM_LOCALID -eq 0 ] ; then

rocm-smi

fi

sleep 2

# !Remove this if using an image extended with cotainr or a container from elsewhere.!

# Start conda environment inside the container

$WITH_CONDA

# MIOPEN needs some initialisation for the cache as the default location

# does not work on LUMI as Lustre does not provide the necessary features.

export MIOPEN_USER_DB_PATH="/tmp/$(whoami)-miopen-cache-$SLURM_NODEID"

export MIOPEN_CUSTOM_CACHE_DIR=$MIOPEN_USER_DB_PATH

if [ $SLURM_LOCALID -eq 0 ] ; then

rm -rf $MIOPEN_USER_DB_PATH

mkdir -p $MIOPEN_USER_DB_PATH

fi

sleep 2

# Optional! Set NCCL debug output to check correct use of aws-ofi-rccl (these are very verbose)

export NCCL_DEBUG=INFO

export NCCL_DEBUG_SUBSYS=INIT,COLL

# Set interfaces to be used by RCCL.

# This is needed as otherwise RCCL tries to use a network interface it has

# no access to on LUMI.

export NCCL_SOCKET_IFNAME=hsn0,hsn1,hsn2,hsn3

# Next line not needed anymore in ROCm 6.2. You may see PHB also instead of 3, which is equivalent

export NCCL_NET_GDR_LEVEL=3

# Set ROCR_VISIBLE_DEVICES so that each task uses the proper GPU

export ROCR_VISIBLE_DEVICES=$SLURM_LOCALID

# Report affinity to check

echo "Rank $SLURM_PROCID --> $(taskset -p $$); GPU $ROCR_VISIBLE_DEVICES"

# The usual PyTorch initialisations (also needed on NVIDIA)

# Note that since we fix the port ID it is not possible to run, e.g., two

# instances via this script using half a node each.

export MASTER_ADDR=$(python get-master.py "$SLURM_NODELIST")

export MASTER_PORT=29500

export WORLD_SIZE=$SLURM_NPROCS

export RANK=$SLURM_PROCID

# Run app

cd /workdir/mnist

python -u mnist_DDP.py --gpu --modelpath model

The script needs to be executable.

The script sets a number of environment variables. Some are fairly standard when using PyTorch on an HPC cluster while others are specific for the LUMI interconnect and architecture or the AMD ROCm environment. We notice a number of things:

-

At the start we just print some information about the GPU. We do this only ones on each node on the process which is why we test on

$SLURM_LOCALID, which is a numbering starting from 0 on each node of the job:if [ $SLURM_LOCALID -eq 0 ] ; then rocm-smi fi sleep 2 -

The container uses a Conda environment internally. So to make the right version of Python and its packages availabe, we need to activate the environment. The precise command to activate the environment is stored in

$WITH_CONDAand we can just call it by specifying the variable as a bash command. -

The

MIOPEN_environment variables are needed to make MIOpen create its caches on/tmpas doing this on Lustre fails because of file locking issues:export MIOPEN_USER_DB_PATH="/tmp/$(whoami)-miopen-cache-$SLURM_NODEID" export MIOPEN_CUSTOM_CACHE_DIR=$MIOPEN_USER_DB_PATH if [ $SLURM_LOCALID -eq 0 ] ; then rm -rf $MIOPEN_USER_DB_PATH mkdir -p $MIOPEN_USER_DB_PATH fiThese caches are used to store compiled kernels.

-

It is also essential to tell RCCL, the communication library, which network adapters to use. These environment variables start with

NCCL_because ROCm tries to keep things as similar as possible to NCCL in the NVIDIA ecosystem:export NCCL_SOCKET_IFNAME=hsn0,hsn1,hsn2,hsn3 export NCCL_NET_GDR_LEVEL=3Without this RCCL may try to use a network adapter meant for system management rather than inter-node communications!

-

We also set

ROCR_VISIBLE_DEVICESto ensure that each task uses the proper GPU. This is again based on the local task ID of each Slurm task. -

Furthermore some environment variables are needed by PyTorch itself that are also needed on NVIDIA systems.

PyTorch needs to find the master for communication which is done through the

get-master.pyscript that we created before:export MASTER_ADDR=$(python get-master.py "$SLURM_NODELIST") export MASTER_PORT=29500As we fix the port number here, the

conda-python-distributedscript that we provide, has to run on exclusive nodes. Running, e.g., 2 4-GPU jobs on the same node with this command will not work as there will be a conflict for the TCP port for communication on the master asMASTER_PORTis hard-coded in this version of the script.

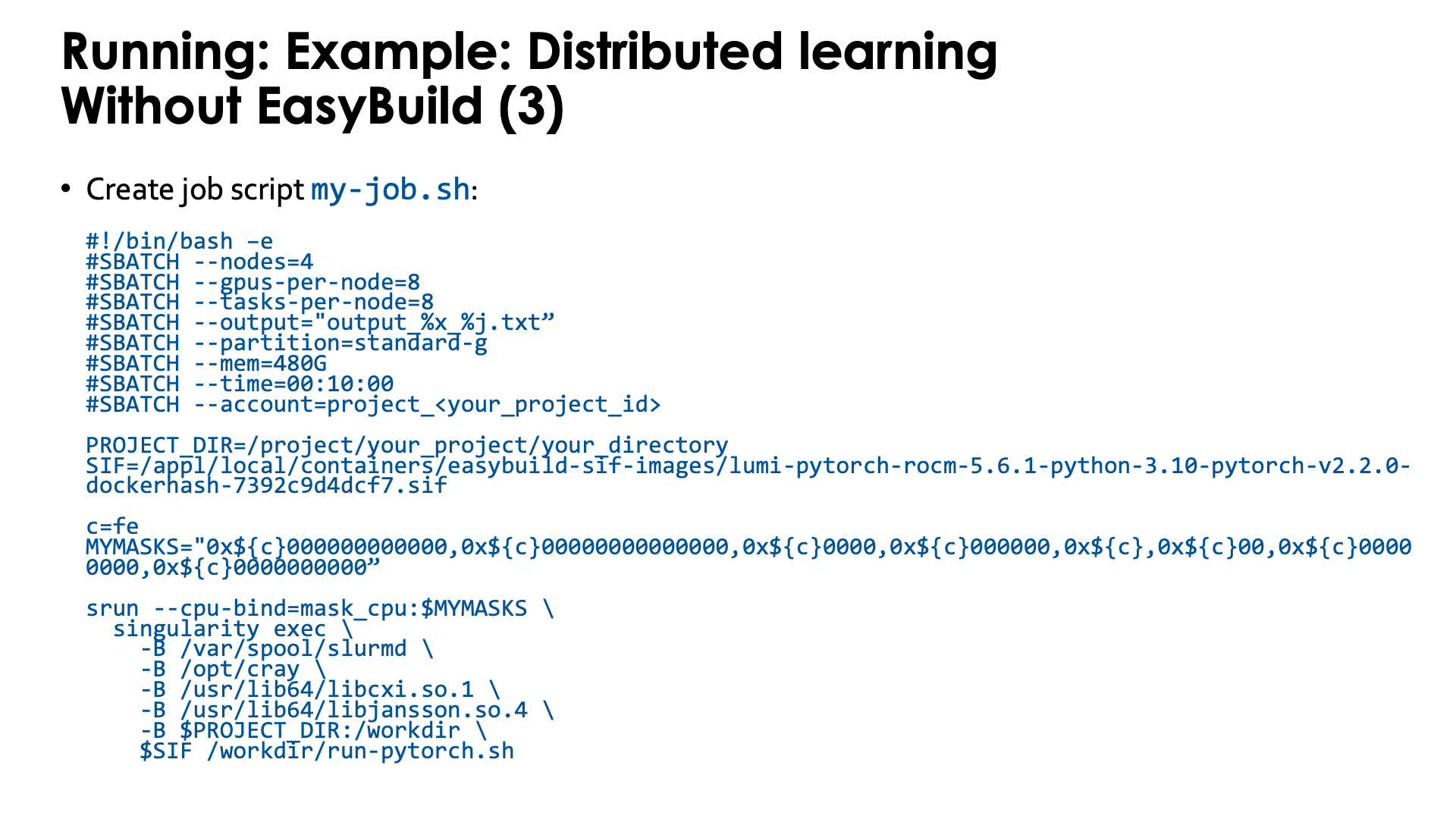

And finally you need a job script that you can then submit with sbatch. Lets call it my-job.sh:

#!/bin/bash -e

#SBATCH --nodes=4

#SBATCH --gpus-per-node=8

#SBATCH --tasks-per-node=8

#SBATCH --output="output_%x_%j.txt"

#SBATCH --partition=standard-g

#SBATCH --mem=480G

#SBATCH --time=00:10:00

#SBATCH --account=project_<your_project_id>

CONTAINER=your-container-image.sif

c=fe

MYMASKS="0x${c}000000000000,0x${c}00000000000000,0x${c}0000,0x${c}000000,0x${c},0x${c}00,0x${c}00000000,0x${c}0000000000"

srun --cpu-bind=mask_cpu:$MYMASKS \

singularity exec \

-B /var/spool/slurmd \

-B /opt/cray \

-B /usr/lib64/libcxi.so.1 \

-B /usr/lib64/libjansson.so.4 \

-B $PWD:/workdir \

$CONTAINER /workdir/run-pytorch.sh

The important parts here are:

-

We start PyTorch via

srunand this is recommended. Thetorchruncommand has to be used with care as not all its start mechanisms are compatible with LUMI. -

We also use a particular CPU mapping so that each rank can use the corresponding GPU number (which is taken care of in the

run-pytorch.shscript). We use the "Linear assignment of GCD, then match the cores" strategy. -

Note the bindings. In this case we do not even bind the full

/project,/scratchand/flashsubdirectories, but simply make the current subdirectory that we are using outside the container available as/workdirin the container. This also implies that any non-relative symbolic link or any relative symbolic link that takes you out of the current directory and its subdirectories, will not work, which is awkward as you may want several libraries to run from to have simultaneous jobs, but, e.g., don't want to copy your dataset to each of those directories.

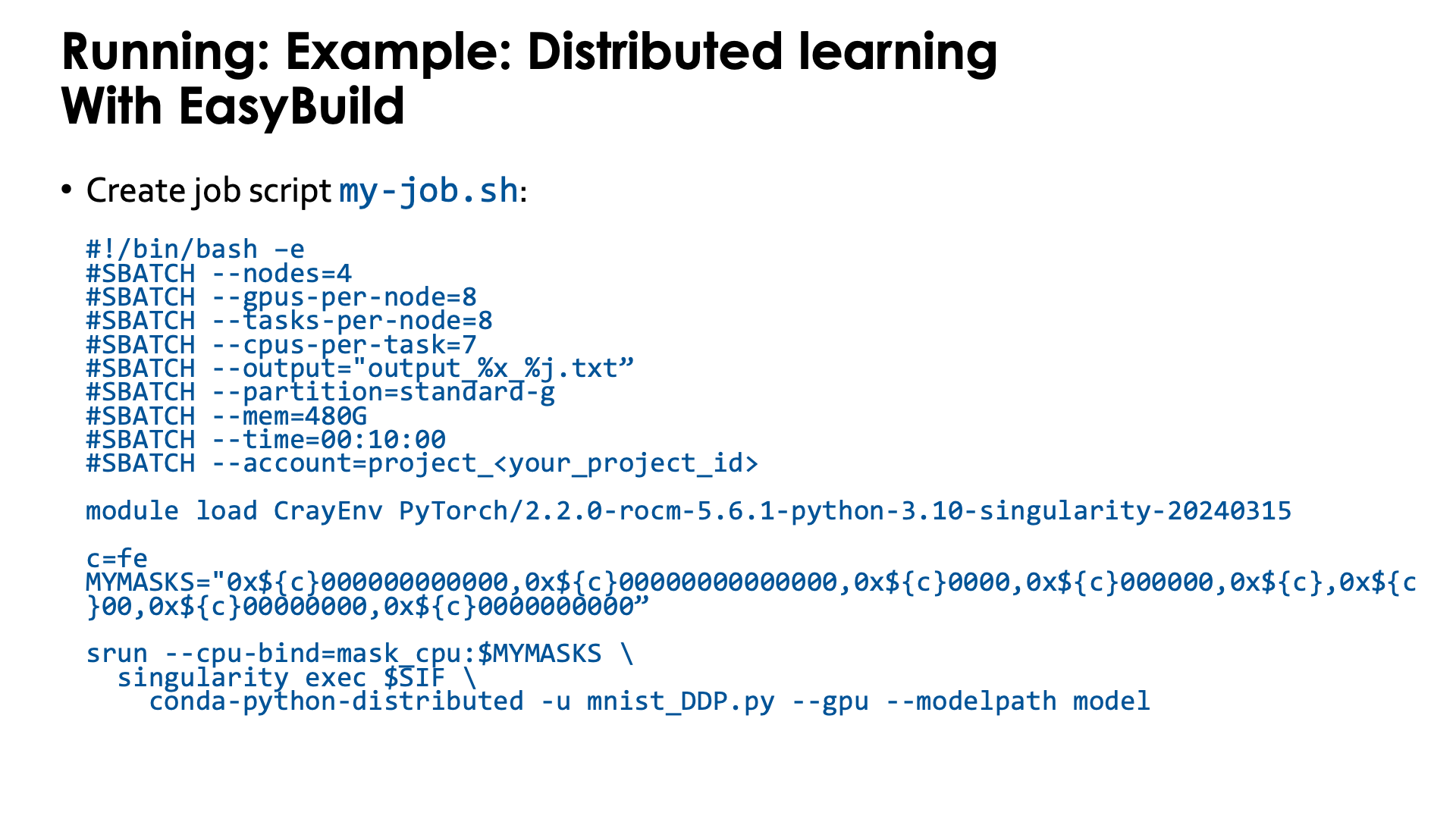

Example: Distributed learning with the EasyBuild-generated module¶

To really run this example, some additional program files and data files are needed that are not explained in this text. You can find more information on the PyTorch page in the LUMI Software Library.

It turns out that the first two above scripts in the example above, are fairly generic.

Therefore the module provides a slight variant of the second script, now called conda-python-distributed,

that at the end calls python, passing it all arguments it got and hence can be used to start other Python code also.

It is in $CONTAINERROOT/runscripts or in the container as /runscripts.

As the module also takes care of bindings, the job script is simplified to

#!/bin/bash -e

#SBATCH --nodes=4

#SBATCH --gpus-per-node=8

#SBATCH --tasks-per-node=8

#SBATCH --output="output_%x_%j.txt"

#SBATCH --partition=standard-g

#SBATCH --mem=480G

#SBATCH --time=00:10:00

#SBATCH --account=project_<your_project_id>

module load LUMI # Which version doesn't matter, it is only to get the container.

module load PyTorch/2.6.0-rocm-6.2.4-python-3.12-singularity-20250404

c=fe

MYMASKS="0x${c}000000000000,0x${c}00000000000000,0x${c}0000,0x${c}000000,0x${c},0x${c}00,0x${c}00000000,0x${c}0000000000"

cd mnist

srun --cpu-bind=mask_cpu:$MYMASKS \

singularity exec $SIFPYTORCH \

conda-python-distributed -u mnist_DDP.py --gpu --modelpath model

So basically you only need to take care of the proper CPU bindings where we again use the "Linear ssignment of GCD, then match the cores" strategy.

Extending the containers¶

We can never provide all software that is needed for every user in our containers. But there are several mechanisms that can be used to extend the containers that we provide:

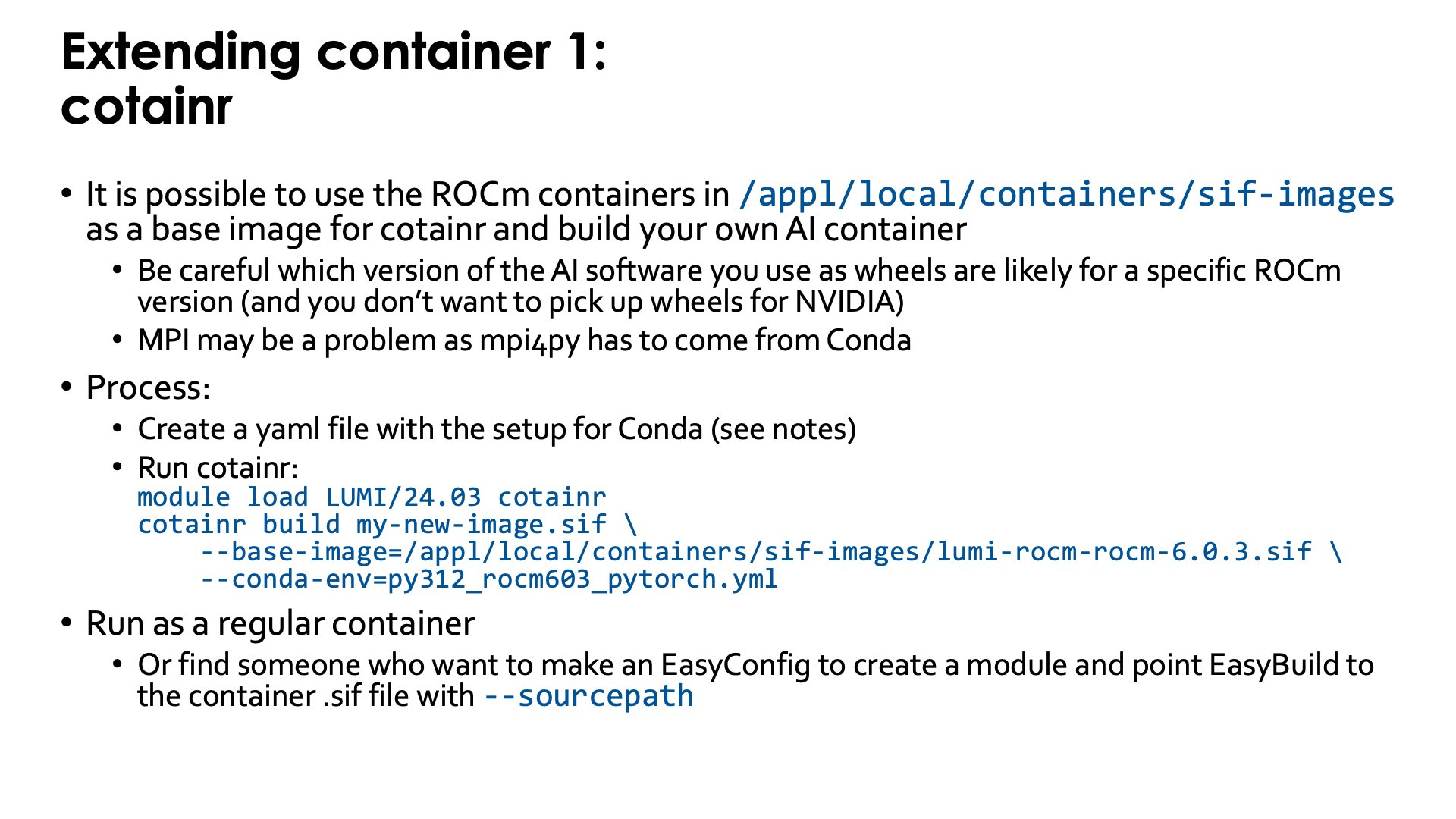

Extending the container with cotainr¶

The LUMI Software Library offers some container images for ROCm™. Though these images can be used simply to experiment with different versions of ROCm, an important use of those images is as base images for the cotainr tool that supports Conda to install software in the container.

Some care is needed though when you want to build your own AI containers. You need to ensure that binaries for AMD GPUs are used,

as by default you may get served NVIDIA-only binaries. MPI can also be a problem, as the base image does not yet provide,

e.g., a properly configures mpi4py (which would likely be installed in a way that conflicts with cotainr).

The container images that we provide can be found in the following directories on LUMI:

-

/appl/local/containers/sif-images: Symbolic link to the latest version of the container for each ROCm version provided. Those links can change without notice! -

/appl/local/containers/tested-containers: Tested containers provided as a Singularity .sif file and a docker-generated tarball. Containers in this directory are removed quickly when a new version becomes available. -

/appl/local/containers/easybuild-sif-images: Singularity .sif images used with the EasyConfigs that we provide. They tend to be available for a longer time than in the other two subdirectories.

First you need to create a yaml file to tell Conda which is called by cotainr which packages need to be installed.

This is also discussed in

"Using the images as base image for cotainr" section of the LUMI Software Library rocm page.

For example, to create a PyTorch installation for ROCm 6.0.3, one can first create the

YAML file py312_rocm603_pytorch.yml with content

name: py312_rocm603_pytorch.yml

channels:

- conda-forge

dependencies:

- filelock=3.15.4

- fsspec=2024.9.0

- jinja2=3.1.4

- markupsafe=2.1.5

- mpmath=1.3.0

- networkx=3.3

- numpy=2.1.1

- pillow=10.4.0

- pip=24.0

- python=3.12.3

- sympy=1.13.2

- typing-extensions=4.12.2

- pip:

- --extra-index-url https://download.pytorch.org/whl/rocm6.0/

- pytorch-triton-rocm==3.0.0

- torch==2.4.1+rocm6.0

- torchaudio==2.4.1+rocm6.0

- torchvision==0.19.1+rocm6.0

Next we need to run cotainr with the right base image to generate the container:

module load LUMI/24.03 cotainr

cotainr build my-new-image.sif \

--base-image=/appl/local/containers/sif-images/lumi-rocm-rocm-6.0.3.sif \

--conda-env=py312_rocm603_pytorch.yml

or, as for the current version of cotainr in LUMI/24.03 this image is actually the base image for the lumi-g preset:

module load LUMI/24.03 cotainr

cotainr build my-new-image.sif \

--system=lumi-g \

--conda-env=py312_rocm603_pytorch.yml

The cotainr command takes three arguments in this example:

-

my-new-image.sifis the name of the container image that it will generate. -

--base-image=/appl/local/containers/sif-images/lumi-rocm-rocm-6.0.3.sifpoints to the base image that we will use, in this case the latest version of the ROCm 6.0.3 container provided on LUMI.This version was chosen for this case as ROCm 6.0.3 version corresponding to the driver on LUMI at the time of writing (early FEbruary 2025), but with that driver we could also have chosen PyTorch versions that require ROCm 6.1 or 6.2.

-

--conda-env=py312_rocm603_pytorch.yml: The YAML file with the environment definition.

The result is a container for which you will still need to provide the proper bindings to some libraries on the system (to interface

properly with Slurm and so that RCCL with the OFI plugin can work) and to your spaces in the file system that you want to use. Use, e.g., singularity-AI-bindings which should work for many cases.

Or you can adapt an EasyBuild-generated module for the ROCm container that you used to use your container instead (which will require

the EasyBuild eb command flag --sourcepath to specify where it can find the container that you generated, and you cannot delete

it from the installation afterwards).

Note that cotainr can build upon the ROCm™ containers that are provided on LUMI, but not

upon containers that already contain a Conda installation. It cannot extend an existing Conda

installation in a container.

Course lecture on cotainr

The "Moving your AI training jobs to LUMI" course has a session "Building containers from Conda/pip environments" (link to the materials of the course in October 2025) with examples and exercises for this approach.

Extending the container with the singularity unprivileged proot build¶

Singularity specialists can also build upon an existing container using singularity build.

The options for build processes are limited though because we have no support for user namespaces or the fakeroot feature.

The "Unprivileged proot builds" feature from recent SingularityCE versions

is supported though.

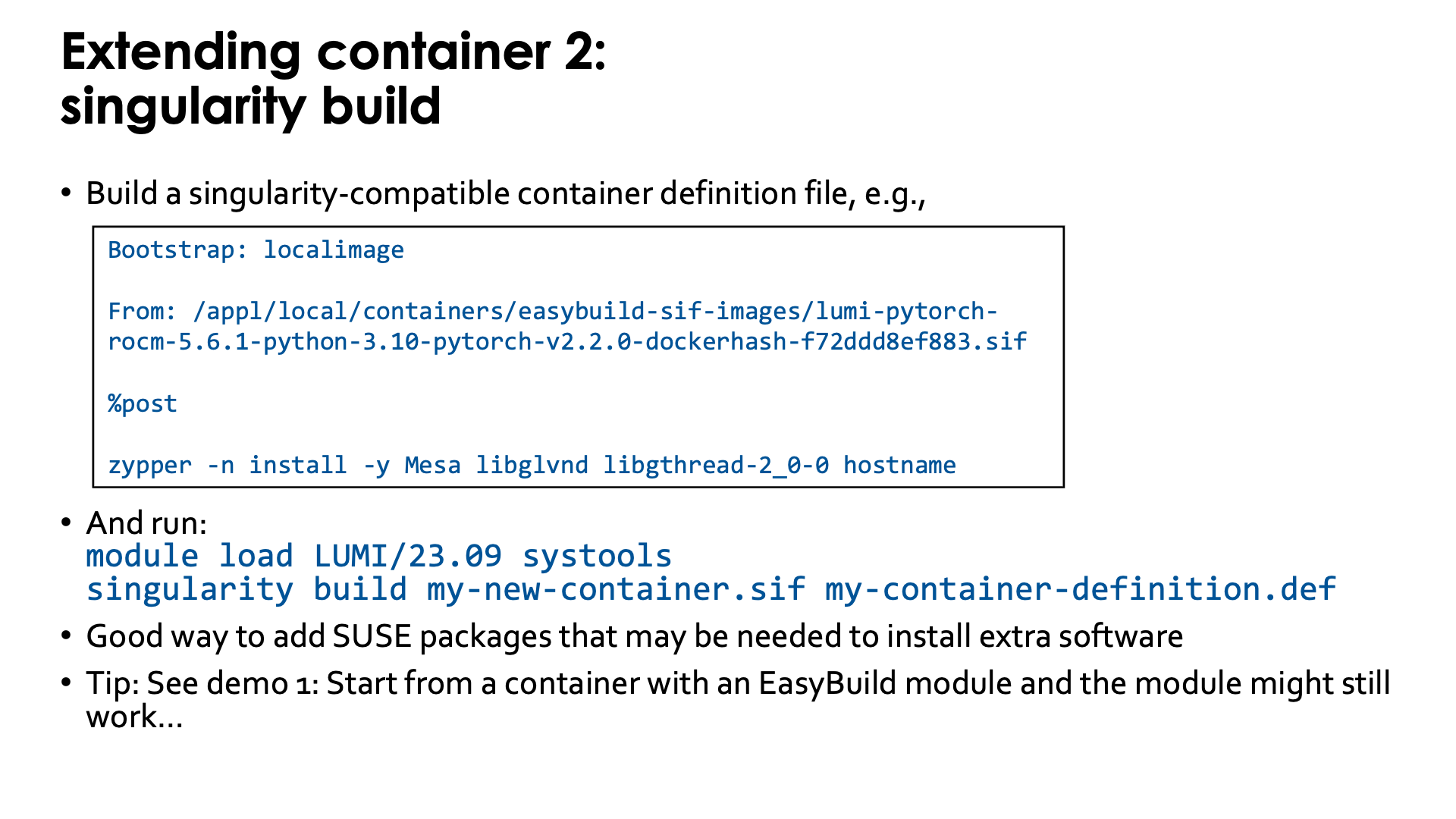

To use this feature, you first need to write a singularity-compatible container definition file, e.g.,

Bootstrap: localimage

From: /appl/local/containers/easybuild-sif-images/lumi-pytorch-rocm-6.0.3-python-3.12-pytorch-v2.3.1-dockerhash-2c1c14cafd28.sif

%post

zypper -n install -y Mesa libglvnd libgthread-2_0-0 hostname

which is a definition file that will use the SUSE zypper software installation tool to add a number of packages

to one of the LUMI PyTorch containers to provide support for software OpenGL rendering (the CDNA GPUs do not support

OpenGL acceleration) and the hostname command.

To use the singularity build command, we first need to make the proot command available. This is currently

not installed in the LUMI system image, but is provided by the systools/24.03 and later modules that can be

found in the corresponding LUMI stack and in the CrayEnv environment or by the PRoot module in all

LUMI stacks and the CrayEnv stack.

To update the container, run:

module load LUMI/24.03 systools

singularity build my-new-container.sif my-container-definition.def

Note:

-

In this example, as we use the

LUMI/24.03module, there is no need to specify the version ofsystoolsas there is only one in this stack. An alternative would have been to usemodule load CrayEnv systools/24.03 -

The

singularity buildcommand takes two options: The first one is the name of the new container image that it generates and the second one is the container definition file.

When starting from a base image installed with one of our EasyBuild recipes, it is possible to overwrite the image file and in fact, the module that was generated with EasyBuild might just work...

Extending the container through a Python virtual environment¶

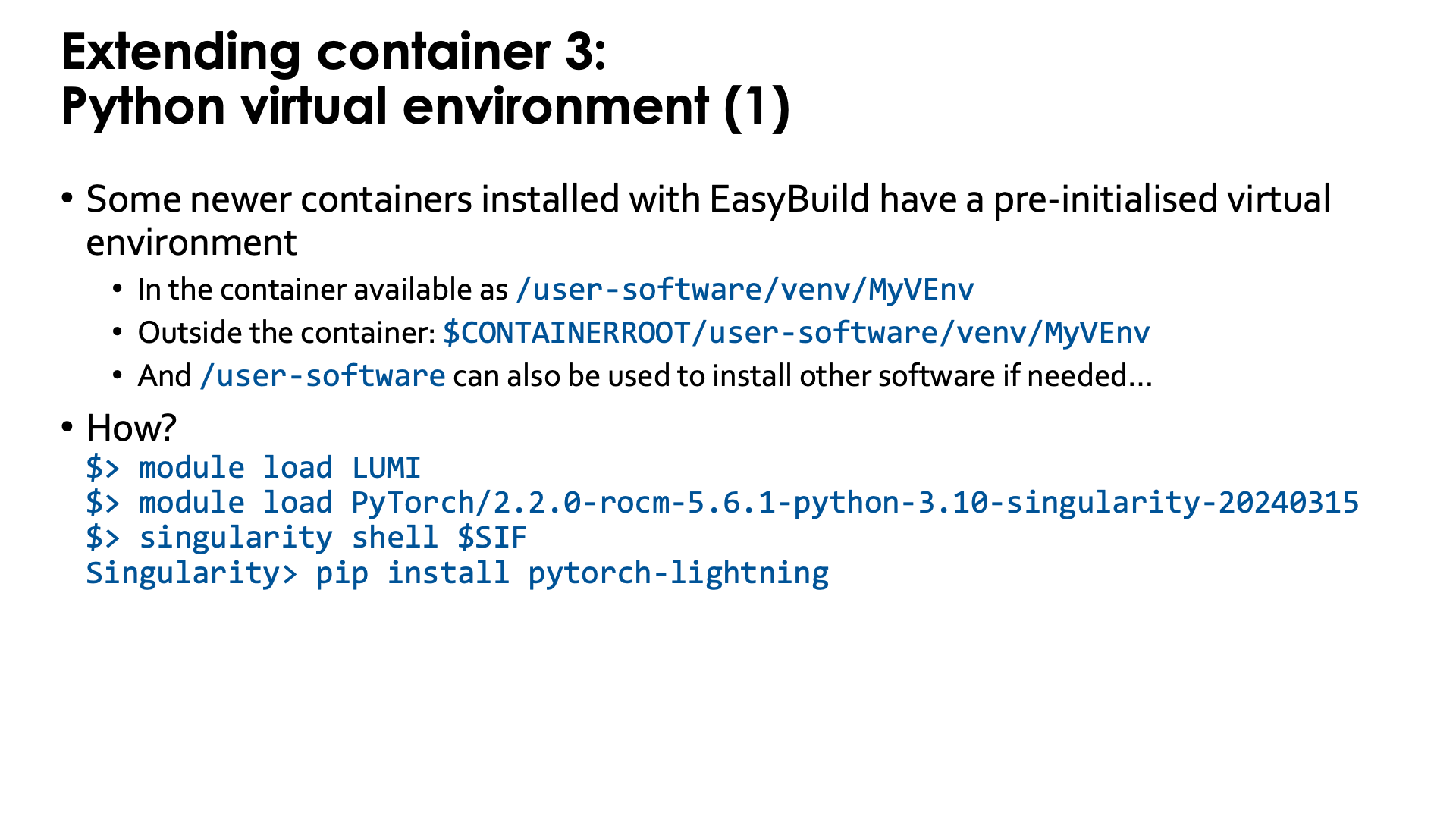

Some newer containers installed with EasyBuild already include a pre-initialised virtual environment

(created with venv). The location in the filesystem of that virtual environment is:

-

/user-software/venv/MyVEnvin the container, whereMyVEnvis actually different in different containers. We used the same name as for the Conda environment. -

$CONTAINERROOT/user-software/venv/MyVEnvoutside the container (unless that directory structure is replaced with the$CONTAINERROOT/user-software.squashfsfile).

That directory struture was chosen to (a) make it possible to install a second virtual environment in /user-software/venv while

(b) also leaving space to install software by hand in /user-software and hence create a bin and lib subdirectory in those

(though they currently are not automatically added to the search paths for executables and shared libraries in the container).

The whole process is very simple with those containers that already have a pre-initialised virtual environment as the module already intialises several environment variables in the container that have the combined effect of activating both the Conda installation and then on top of it, the default Python virtual environment.

Outside the container, we need to load the container module, and then we can easily go into the container using the SIF

environment variable to point to its name:

module load LUMI

module load PyTorch/2.6.0-rocm-6.2.4-python-3.12-singularity-20250404

singularity shell $SIF

and in the container, at the Singularity> prompt, we can use pip install without extra options, e.g.,

pip install pytorch-lightning

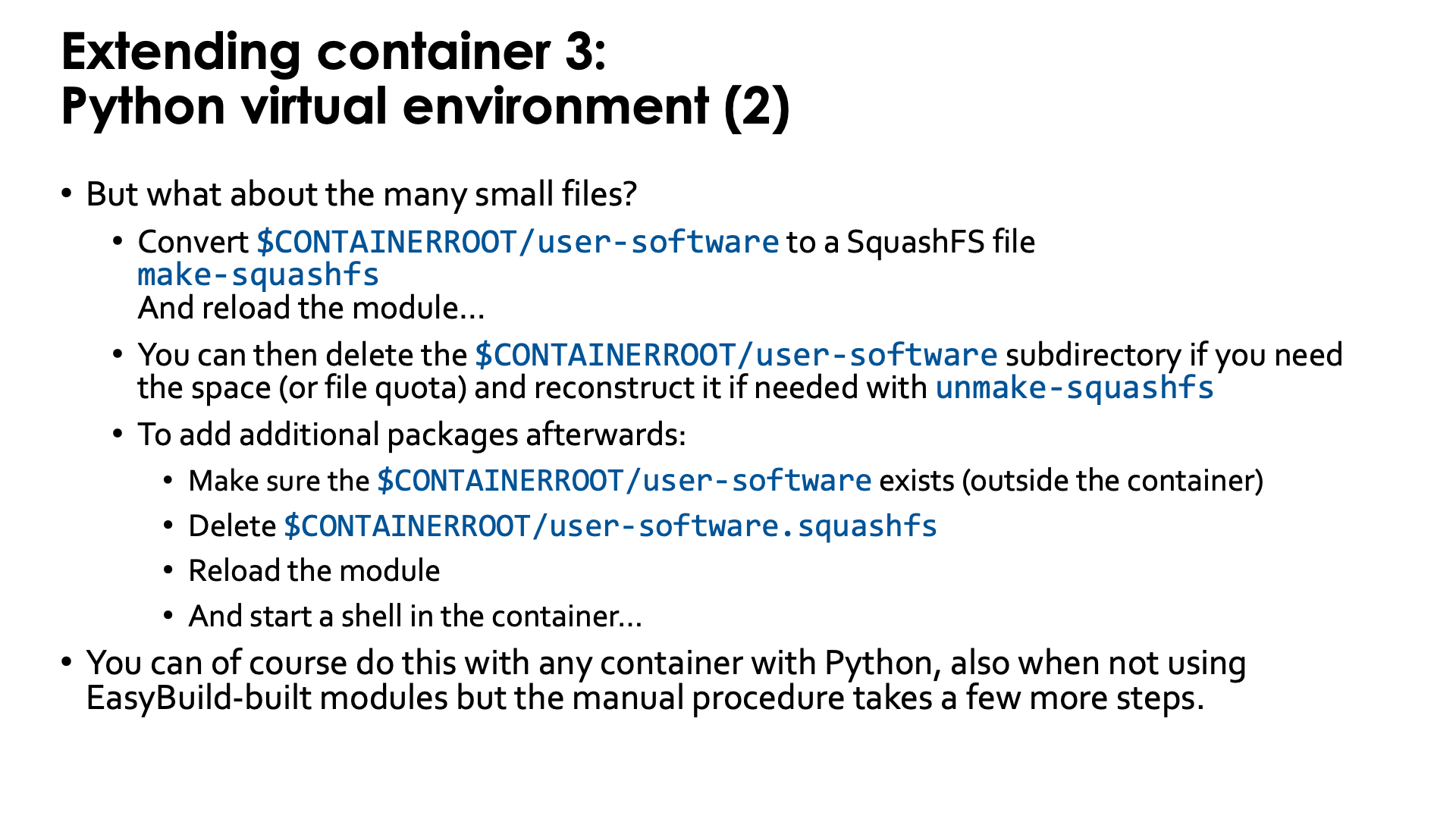

As already discussed before in this session of the tutorial, such a Python virtual environment has the potential

to create a lot of small files in the Lustre $CONTAINERROOT/user-software subdirectory, which can wipe out

all benefits we got from using a container for the Python installation. But our modules with virtual environment

support offer a solution for this also: the make-squashfs command (which should be run outside the container)

will convert the user-software subdirectory in $CONTAINERROOT into the SquashFS file user-software.squashfs

which, after reloading the module, will be used to provide the /user-software subdirectory in the container.

The downside is that now /user-software is read-only as it comes from the SquashFS file. To install further

packages, you'd have to remove the user-software.squashfs file again and reload the container module.

Currently the make-squashfs file will not remove the $CONTAINERROOT/user-software subdirectory, but once

you have verified that the SquashFS file is OK and useable in the container, you can safely delete it yourself.

We also provide the unmake-squasfs script to re-generate the $CONTAINERROOT/user-software subdirectory

(though attribues such as file time, etc., will not be the same as before).

It is of course possible to use this technique with all Python containers, but you may have to do a lot more steps by hand, such as adding the binding for a directory for the virtual environment, creating and activating the environment, and replacing the directory with a SquashFS file to improve file system performance.

Conclusion: Container limitations on LUMI¶

The idea of "bring your own userland and run it on a system-optimised kernel" idea that proponents of containers promote, has two major flaws

-

Every set of userland libraries comes with certain expectations for kernel versions, kernel drivers and their versions, hardware, etc. If these expectations are not met, the container may not work at all or may work inefficiently.

This is particulary true for ROCm™ support as each version of the ROCm™ libraries only works with a limited range of GPU driver versions. If the ROCm™ libraries in the container are too old or too new for the driver on the system, the container will not work. As the ROCm™ ecosystem is maturing, the range of driver versions that are compatible with each ROC™ version is growing, but this issue will likely never be completely solved.

-

Support for specific hardware is not done in the kernel alone. Most of the optimisations for hardware on an HPC system are actually in userland.

-

As most of the time of an application is spent in userland, this is where you need to optimise for a specific CPU and GPU. If a binary is not compiled to benefit from the additional speed of new instructions in a newer architecture, no container runtime can inject that support.

-

Support for the SlingShot network, is in the libfabric library and its CXI provider, which are userland elements (and the same holds for other network technologies).

Container promoters will tell you that is not a problem and that you can inject those libraries in the container, but the reality is that that strategy does not always work, as the library you have on the system may not be the right version for the container, or may need other libraries that conflict with the versions in the container.

Likewise, for containers for distributed AI, one may need to inject an appropriate RCCL plugin to fully use the Slingshot 11 interconnect.

-

The support for building containers on LUMI is currently limited due to security concerns. Any build process that requires elevated privileges, fakeroot or user namespaces will not work.